24 July this year sees the fifth anniversary of the passing of Chiwoniso Maraire, one of the world’s greatest musical talents, and revered as the Queen of Mbira in Zimbabwe and elsewhere. Born 5 March 1976, Chi died in 2013, aged only 37, the same age as Alberta, my ex-wife, at that time. I mention this because they were school-mates in Mutare for a while. My introduction to Shona culture and music owes much to her, and I added considerable efforts myself, reading and doing research, to the point of learning to play songs by Oliver Mtukudzi and, of course, Chiwoniso. I explored Zimbabwean music more and more, and Chi has since become a musical icon for me. Her music speaks to me more than many others. It is a sorrowful case of historical irony that I didn’t know her when she appeared at the Würzburg Afrikafestival in 2011. Some of my favourite live recordings were taken there.

maiChi

Chiwoniso (Shona ‘light, torch’) is the daughter of Chengeto Linda Nemarundwe (customarily named maiChi in Shona culture) and Dumisani Abraham Maraire, a celebrated master of mbira. Her dad must have been very proud of his daughter and student, who started playing mbira at the age of four. Around that time, her dad released an album called Chiwoniso: Music of Zimbabwe (1979). Cornerstones of her biography in short (find a long version here): a childhood spent in Washington state in the USA, the family first returns to Zimbabwe in the early 1980s. Chi makes her debut in 1986, on an album the ten-year old recorded with her parents, called Tichazomuona (‘We shall see you’).

The song and its roots in Shona culture and Christiantiy and notably in the Maraire family is quite indicative of Chi’s musical career, even though it is her first recording:

“It was an original gospel song but one should listen to the rendition which father and daughter had put in it,” he [poet Chirikure] said. “Arrangement and the balance in terms of content, the touch on Christianity and Shona beliefs was awesome.

Chiwoniso threw names of departed relatives in the song, it was an intricate balance between Christianity and traditional African religion. And yet it is a very original Christian song. As complicated as it is for a young girl to have mastered the song and go into the studio and record it in a time of analogue recording, it was so smooth and natural it flows.”

He added: “But when you listen closely it tells you of something that the Maraire family would have let develop in her. But you cannot plant a seed in the desert and it grows, she was a fertile spiritual being placed in the right arms and the right moment. The tree was planted at the right time and it developed and matured. The tree that we are celebrating now brought out the fruits that we are enjoying now and the world is enjoying.” (source)

Chi had followed her dad’s example and played the mbira nyunga-nyunga (‘sparkle-sparkle’). While her commitment to Shona culture and traditions, and especially to the mbira, grew stronger and stronger, Chiwoniso was just as ready to innovate and stay in tune with current developments. Thus she hit centre stage in the Zim music scene in around 1990 when she left her distinct mark as lead vocalist of Zimbabwean’s first hip-hop outfit, A Peace of Ebony. She must have been the first to mix mbira-playing with hip-hop rhythms, and “Vadzimu” is deeply inspired by the spiritual history of the Shona. The lyrics make references to Nehanda and Chaminuka, spiritual ancestors of the Shona as well as, in their reincarnations in the nineteenth century, famous leaders in the first chimurenga, the liberation struggle against the British colonizers. Both appear again and again in Chiwoniso’s later songs.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vWvSjX49aKo

Thus, Chi’s music inadvertently became political: Shona tradition did not promote women as mbira players, though in the late twentieth century some women had become famous as mbira artists, notably Stella Chiweshe and Mbuya Beuler Dyoko, who was the first woman to make a professional mbira recording in the 1960s. Chiwoniso’s choice of the mbira nyunga-nyunga may not only have been motivated by the fact that her father popularized this instrument against the more traditional mbira dzavadzimu.

“He [her father] did not care whether the instrument was played by a man or a woman. To prove his point, he taught his own daughter, Chiwoniso, to play the mbira,” said [music writer Fred] Zindi. (source)

Nyunga-nyunga being less rooted in Shona spiritual traditions likewise may have facilitated the use of the instrument by a woman and outside of more traditional contexts. Having said that, as far as I can tell Chiwoniso always considered nyunga-nyunga as suitable for spiritual music such as “Chaminuka”.

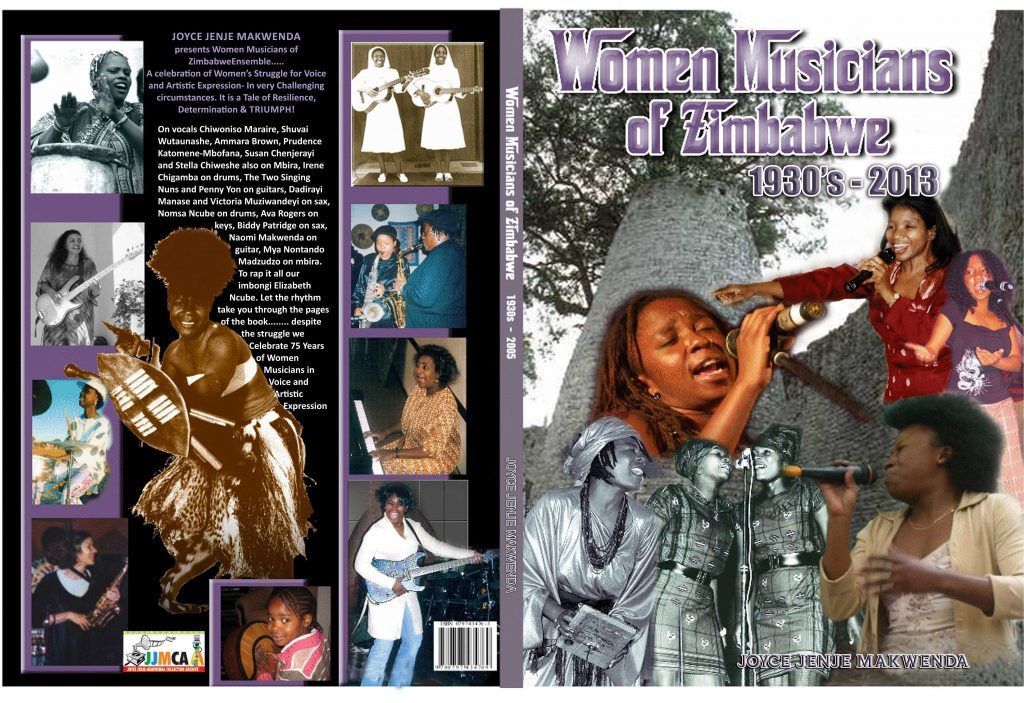

Joyce Jenje Makwenda (2017)

It goes without saying that in the colonial context traditional African culture and music in particular lent themselves powerfully to fight white supremacy and create an identity which helped build confidence. Thus mbira music and music inspired by it, such as the guitar riffs in Thomas Mapfumo‘s chimurenga music played an important role in the struggle for independence, a role that arguably reached out into post-Independence Zimbabwe.

Chiwoniso was aware of the political implications of her music in Zimbabwe under Mugabe and his ZANU-PF, and she was aware of the role traditional spirituality could play in modern Zimbabwe. Here’s a good interview in which she shares some of her views in her role as a “vessel”.

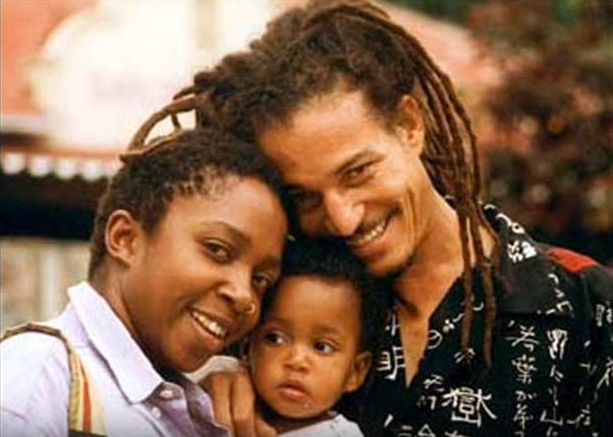

In the mid-90s, Chi joined Andy Brown & The Storm, one of the most successful bands in the 1990s in Zimbabwe. Andy and Chi would marry later on, and had two children, Chiedza and Chengeto. Chi partook in the success of Andy’s band, and she pursued a very successful solo career with much international acclaim since her album Ancient Voices (1998). She formed other projects such as Vibe Culture and The Collaboration, worked and performed together with saxophone player Max Wild, with Mari Boine, Sinead O’Connor and others on Make Me a Channel of Your Peace, as well as with Joy Denalane in Germany, for instance for “Four Women”.

A joint project with Comrade Fatso and Chabvondoka, the song “Bread and Roses” (2009) talks about how the Zimbabwean government cracked down on the numerous street vendors how trying to make a living in a poverty-stricken society at the height of the economical crisis. Chi provides the background voice to the song, chingwa nemaruva (bread and roses), as well as on “House of Hunger”, idzimba ya nzara.

Despite their successful careers, it sounds as if a curse is hanging over their family. In March 2012, Andy dies. In an article published last year, five years after his death, a rather dramatic family history comes to light, a story of drama, pain and tragedy.

Chiwoniso at Andy’s coffin

And then the mbira fell silent. Chiwoniso died little more than a year later of pneumonia in hospital in Chitungwiza, a high-density suburb of Harare. Not the place where you’d expect an acclaimed musician to spend her last ten days. The circumstances of her death seemed obscure at first, and much doubt and mystery was created in the media. But sensationalist newspaper headlines were eventually answered by Chi’s brother, Tendai. May Chi and her family find peace now.

She lies buried alongside her father in Chakohwa village, near Chimanimani. Read how Hugh Masekela visited the tomb of her father and hers here.

Shortly after her passing, mbuya Stella Chiweshe gave this tribute to her at Harare’s Book Cafe – deep Shona spirituality:

Shortly before her passing, on 22 January 2013 (yes, coincidentally my birthday 😉 ), Chiwoniso gave this inspiring interview which allows an insight into her spirituality. It was to be her last, and is accompanied by one of her most spiritual songs, a traditional, Vana vanogwara (mudzimu dzoka) – the children are crying, return great spirit.

The tragedy doesn’t stop. Two years after Chi’s passing, her and Andy’s oldest daughter, Chiedza, apparently overwhelmed still by the loss of her mom, committed suicide at the age of 15. As if this wasn’t tragic enough, until last May, her ashes have remained unburied. Read more here. Here’s a lullaby sung by Chiwoniso, in which voices her best wishes to her two Chiedza and Chengeto: Chinyarara mwana wangu, Usa cheme ini ndiripo …

[from the translation by Tsutomu Kimura]

[from the translation by Tsutomu Kimura]

Keep silent my children

Do not cry whilst I am here

I will hold you in [my] own hands

Do not cry

…

Do not cry

Hey you Hey you Hey you

…

Be quiet Be quiet Be quiet Be quiet my baby Chengeto

Mother loves you where you are

Keep silent my children

Do not cry

Be quiet Be quiet Be quiet Be quiet my baby Chiedza

You are an angel from heaven

Keep silent my children

Do not cry

Hey you Hey you Hey you Keep silent

Here is from another helpful commentary, by Ivor Jones: This is a traditional Shona lullaby sung by mothers to put crying children to sleep or comfort them when not they are not feeling well. But this plaintive melancholic lullaby has double function too. Mothers tended to sing this lullaby when they were deeply unhappy about something. It was always their tears and sorrows they were also trying to soothe or mollify. A woman’s lot is not often a happy one. This lullaby therefore served a double purpose – to comfort a crying child and to bring fortitude and strength to the mother as well. As the child slowly drifts to sleep the mother’s face will be saturated in tears overwhelmed by her own emotions. For this is not just a lullaby to put a crying baby to sleep (Chinyarara mwana wangu, Usa cheme ini ndiripo, Ndokutora mumaoko angu, Usa cheme. Be quiet my child, Do not cry when I’m there (for you), I will take you in my arms (or I will cradel you in my arms) Don’t cry.) This is a mother also giving succour to her own spirit to be strong (Ehuwe, ehuwe. Ehuwe, ehuwe, Usa cheme iwe). The words “usa cheme iwe” after the “ehuwe” are to herself. She needs to be bold, strong and resourceful to confront daily hardships and pain. Chiwoniso’s in this song is going through the same emotions. That is why it is so powerful and tugs at you as well. We sense her sorrow, melancholy, unhappiness. She sounds too plaintive, too fragile, almost too tortured by something, Is it the child she is comforting or herself?

* * *

UPDATE Great obituary (in German) here

* * *

Meanwhile, Chiedza’s younger sister, Chengeto, seems to be more fortunate. She successfully pursues a career in the music business, as a solo artist or in joint projects with her very popular aunt, Ammara Brown.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nplO2rUDIPw

* * *

Chiwoniso’s legacy

… is her music, in which her spirit stays with us. Some years ago, I completed the discography on Wikipedia, but have since discovered new material. I will update the information soon! And, yes, I’ve been trying to play her music, started learning nyunga-nyunga, and yes, I’m getting there 😉

Needless to say, others have been there long before me, and are doing much much better. Here are two, Tanyaradzwa Tawengwa (whose choral drama Dawn of the Rooster you don’t want to miss!), and of course Hope Masike. Both accomplished musicians in their own right, though they won’t mind (and Tanyaradzwa makes it explicite) to be seen as part of Chi’s legacy.

Vibe Culture, without Chi

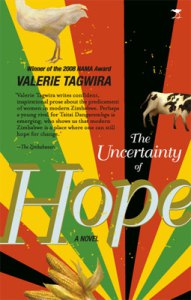

Chiwoniso has made appearances in novels, too. Here are two:

But now it’s time for you to explore her music yourself. … You’re welcome!

Rebel woman

Chaminuka

In this life

Sinu (Vana vanogwara)

Chi’s work with Hans Lüdemann and the Trio Ivoire extended over years. One of my favourite pieces from their album Across the Oceans is “Tije-kije”. A powerful song, with only piano accompaniment, it intrigued me, I needed to find out about its meaning. Eventually I contacted Hans, who told the story of how, in 2008, at HIFA Chiwoniso saw the performance of a South African jazz musician, and copied the lyrics as she heard them. Allegedly, they were about a locust threatening the harvest of the people – how fitting in the Zimbabwe of 2008! However, her lyrics for the song, copied by ear, are not in any actual language. It took me a while, and through my friends in South Africa we eventually found someone who recognized the melody as a song from his childhood, Tsie, in seTswana.

Here is Chi with a version of Vana vanogwara with Trio Ivoire and Aly Keita on balafon.

Iwai nesu (Be with us)

Iwai nesu, mwari baba

Mwari baba, iwai nesu

Kutungamira nekutungamirwa

Tiri vana venyu

Mukutawura nemuku homoka

Tiri vana venyu

Mukufunga nemukurota

Tiri vana venyu

A really good cover version:

Mai (fambai zvakanaka)

For many, her most popular song, dedicated to her mother who had passed away. I find, we can here Chiwoniso beautifully through the words of this song. So, fambai zvakanaka, Chi! See you in the next world 😉

Sometimes I imagine I hear your voice

in the trees whispering

ooohhhhhhhhh

aaahhhhhhhhh

you had this way of understanding

anything we said

time was there whenever we needed

ohhhh anything we said

we search the world over for your smile

though we know you are gone

you will always be in our hearts

ohhh we won’t be long

no no no till we are together

no we won’t be long

mai fambai zvakanaka

mai tichazomuona

mai fambai zvakanaka

mai tichazomuona

mai fambai zvakanaka

mai tichazomuona

mai fambai zvakanaka

mai tichazomuona

I imagine I hear your voice

mai tichazomuona

I imagine I hear your voice

mai wonsio

mai fambai zvakanaka

mai tichamuona

mai fambai zvakanaka

mai tichazomuona

mai fambai zvakanaka

mai tichazomuona

mai fambai zvakanaka

mai tichazomuona

yoooooyoyooooo

mai fambai zvakanaka

mai tichazomuona

mai fambai zvakanaka

mai tichazomuona

Fambai zvakanaka

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J7zD4VoawZ4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BdyWMa0rHow

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-q_bcnOif1w

Pingback: Phillippa Yaa De Villiers for Chiwoniso - VuyoGoVuyoGo

Pingback: Mbira (in)tangibility - VuyoGoVuyoGo