… and some research, mostly done in my “home office“. But teaching is what I came here for, on my INSPIRE scholarship.

Ngiyakwemukela, here’s UJ!

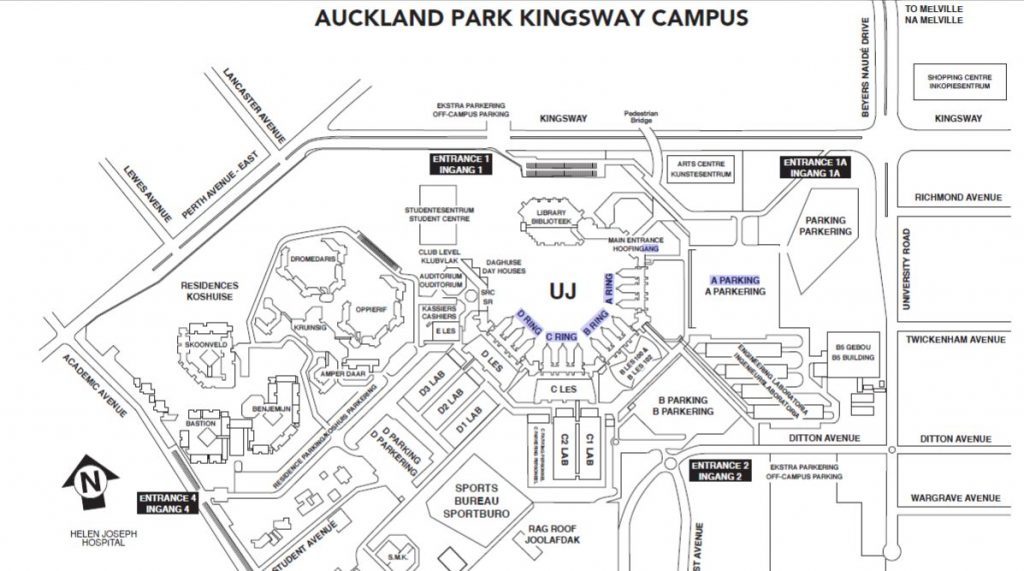

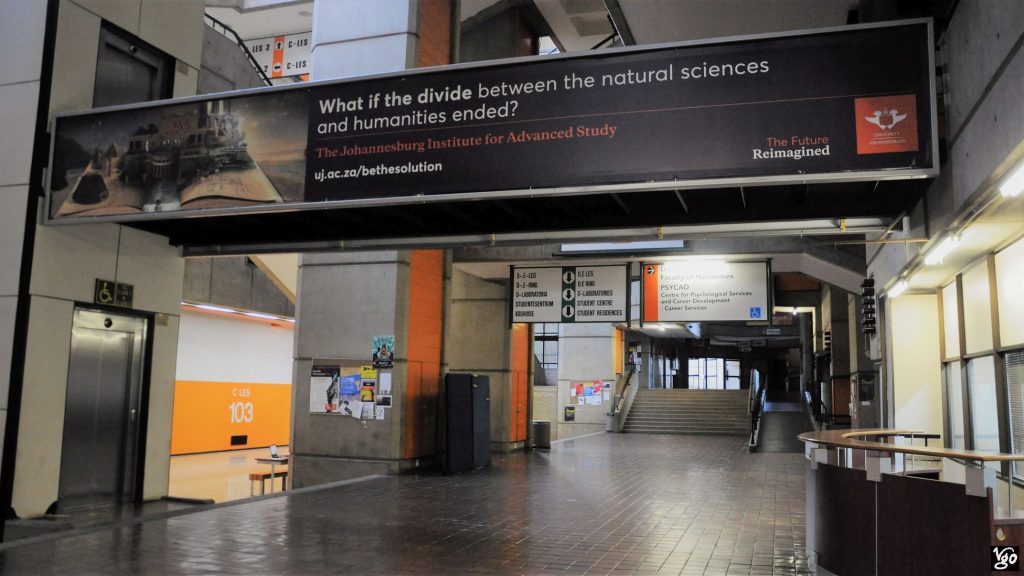

The central building at Auckland Park campus is a concrete monster, forming a half circle of sorts. Its various sections are referred to as “ring”, so the ten-odd offices that are the Department of English are on level 7 in the B ring, until last year sandwiched between African languages and German/Greek/Latin, the latter now extinct. The concrete mass is matched by bureaucratic hurdles that pile up between you and whatever you want to get done. When a prospective student has mastered his or her “matric” (the South-African equivalent to a-levels), they may realize that this is the real exam, with specializations in patience and stamina. Of course, I am exaggerating here. Once you are registered you get an access card, and with this in your hand you join the queue at the gates to register your finger print and walk in. “Walk-ins” by unregistered students are the horror for admin here – after all, you have to pay to be allowed in, and the fees are rather high. Which is why many believe that #FeesMustFall (see protests at Wits Uni here).

A sign, now removed, promising German, Greek and Latin teaching

UJ emerged from the Rand Afrikaanse Universiteit, an Afrikaans speaking institution, in 2005. It is a big university (50,000 students) with four campuses in the metropolitan area (Johannesburg and Soweto, with a combined population of about 10 million). UJ reflects the challenges the whole country is facing. One success story is linked to the increased number of black students at UJ: from 60% in 2005 to 86% now. Many black undergrads at UJ come from unprivileged backgrounds, and the majority of them are the first in their families to aspire to, and to achieve, higher education degrees in a country where racial divides are still a huge problem.

More numbers: the Department of English here has some eight colleagues on permanent posts, who cater for some 1,500 or so students (compare Göttingen, with ca 40 : 900). The pressure is high on everyone, and I’m told that five colleagues resigned over the last year or so, and while I’m here another two are leaving. As there are apparently no replacements, the workload for the rest increases. In practice this means that teaching mostly happens in rather big lecture halls, and an Introduction course typically has 300+ students, with numbers dropping to around 100 in classes for third-year students. The courses are shared by staff, so one prof is teaching a group for some three or so weeks, and then they swap. This is made possible through highly standardized contents. Think of this what you will, it is the only way to cope with the situation as is. Besides, it also makes it possible to announce books to be read for the next term, and to order them for the bookshop. Many students will have to buy a book when the money is there, not just at any time. So good planning is key.

Much work is done by tutors, mostly students doing honours and MA degrees. A number of times I found myself sitting in the tutorial room, and couldn’t help eavesdropping on these small-group tutorials. The tutors did a really great job in walking their three or so students through written assignments, covering stylistics, embedding quotes and such like. What I always found very charming is the “yeah” from the mouths of students who would be taking in whatever they can. I have often noticed a great readiness, for better, for worse, to accept advice and new information by Africans across the region, and I find it here again. It is a great quality, and betrays ambition and willingness to improve oneself and can have great effect if it is matched by the teacher’s or tutor’s responsibility. It is detrimental though when it gets abused, as seems to happen in many cults and churches, and also in the political arena. Hierarchies matter in African cultures, and as a teacher you are higher up than others. This reflects in some students leaving you with saying “Thank you, teacher”, or security guards greeting me with “Good afternoon, prof”.

Things are significantly better on post-grad level, with around 10 or so students per class, primarily because most students would not and could not prolong their education beyond the BA threshold. One reason: studying here is expensive (around EUR 3,000+ counting only tuition fees). Talk about privilege or the lack of it, huh!? Here is one example to illustrate the struggle of some students here:

Does that lower the quality of teaching? Yes and no. For one, and that is my personal experience: students whose families pay those fees are keen to make the most of every session, and I am impressed about the discipline that I have found in a room with close to 100 students in it. Somebody start chatting, and immediately a crowd of some ten students will shush them! On the other hand, not everyone is able to buy books, or they have to drop out for a year because mom and dad lost their job (unemployment rate in SA is currently at ca. 28%, youth unemployment at a shocking 39% and rising).

UJ is trying to quite a number of students through bursaries. This source says that “In 2016, the University’s Missing Middle campaign secured over a R100M [ca EUR 7 Mio] through which the University, working with the UJ Student Representative Council (UJSRC), were able to assist over 3000 students by paying their registration fees and minimum initial payments for the 2016 academic year. However, students require support for the balance of their fees and other needs. The average cost of funding a UJ student for a year currently stands at R85 000 [ca EUR 6,000]. This includes tuition, accommodation, books and other living allowances.”

Last year, shortly before he submitted to the forces urging him to step down, former president Zuma announced free education in SA, which caught many by surprise. Howver, as of this year students from households with a gross income of no more than R350,000 (EUR 25,000) qualify for free education (this is how I understand it anyway – more here).

Another mirror of the country at large: studying here is not free from unfairness, even if you are among the lucky ones who’ve made it in. For instance, if you’ve sat for an exam but fail to pay the last instalment of your fees, the exam result will not be revealed to you until the money has been paid. Now imagine your parents have no job for a year or two, you may have to wait for that time and, worst-case scenario, learn eventually that you didn’t pass. I consider this practice extremely unfair, and my gut feeling tells me it would be illegal in Germany.

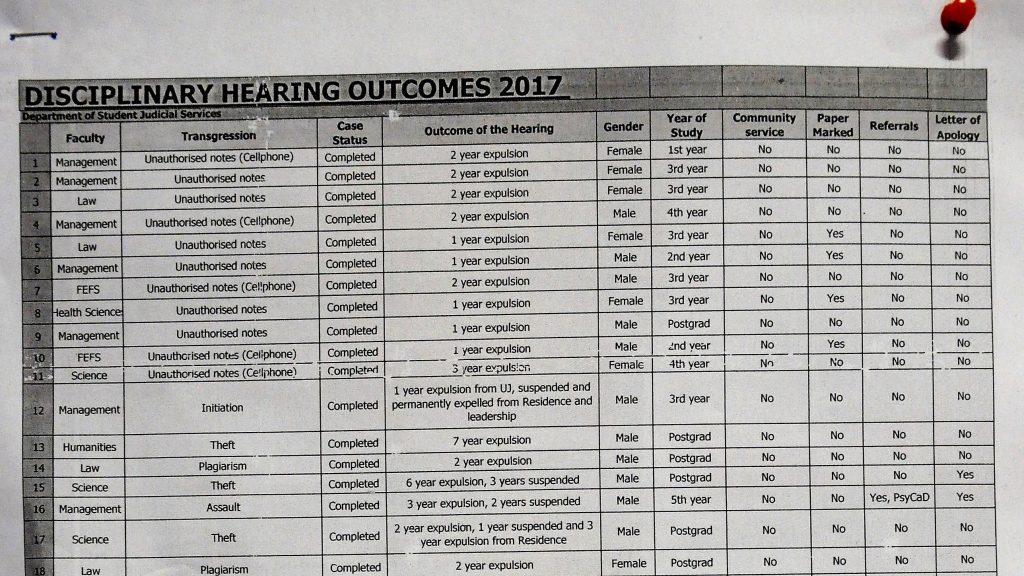

UJ knows no fun when it comes to academic conduct. Here’s the latest statistics about severe offenses to their code of conduct, and the measures are harsh (click to enlarge).

Recent challenges are of a rather ideological nature linked to the history of the country and the continent at large: English is a national language, yet only one of eleven, and disputes about language and education can become very heated here. See some here (school kids and Afrikaans) and here (commentary on the 2017 Revised Language Policy for Higher Education). One of my students, she said she’s from a rather racist white Afrikaaner family, related to me how difficult it was for her to sit in a class with easily 95% black fellow students who have no difficulty following the remarks made in isiXhosa or isiZulu by a – likewise black – teacher. What a great opportunity, I suggested to her, to start seeing things from the other side. After all, for a century or more blacks had to learn Afrikaans and English if they wanted to get anywhere with their lives.

Recent challenges are of a rather ideological nature linked to the history of the country and the continent at large: English is a national language, yet only one of eleven, and disputes about language and education can become very heated here. See some here (school kids and Afrikaans) and here (commentary on the 2017 Revised Language Policy for Higher Education). One of my students, she said she’s from a rather racist white Afrikaaner family, related to me how difficult it was for her to sit in a class with easily 95% black fellow students who have no difficulty following the remarks made in isiXhosa or isiZulu by a – likewise black – teacher. What a great opportunity, I suggested to her, to start seeing things from the other side. After all, for a century or more blacks had to learn Afrikaans and English if they wanted to get anywhere with their lives.

Then there’s the aim for a decolonized curriculum, which leaves English and English lit in precarious positions, after all it was a language of suppression, but less so than Afrikaans as it was also a lingua france across much of eastern and southern Africa. So, how colonial, how foreign, how native is English literature? Or how do you teach Shakespeare’s “Hamlet”, in which king Claudius is unfavourably compared to a “moor”, in front of a class of “black” kids who no longer want to hear that being “black” is being less, let alone ugly. Dump good ol’ Willie, the racist? BTW, unlike in the USA, people here don’t create a taboo around terms such as “black”, “white” and “coloureds” – I suppose in an understanding that your attitude does not simply change by suppressing or substituting a word. Hence, like everyone I know, I use “black” and “white” quite comfortably here, seeing in it a reflection of social and historical reality, not a racial one based on a perceived colour. And after all, we know that black is beautiful, so I’m happy to join in celebrations of “blackness” in Wakanda. Don’t know what I’m talking about? Or in doubt? Watch the video here.

Talking about culture – one of the liveliest moments in the class room was sparked by a student’s remark. I had just ripped Hamlet to pieces for gaslighting and generally abusing Ophelia emotionally. So this guy speaks up saying that if a girl rejects a guy, surely she is responsible for his subsequent actions. Immediate protest by many of the black girls in the room, and we found a way to refine this debate, which easily touched some sensitive cultural issues. Indeed, the next day a student approached me, female, third generation Indian in the country, saying that it would be quite unusual if they were asked not to side with the main male character, coz this is what you normally do, don’t you?! Side with the men, regardless. She highlighted difference in “culture” as the probable cause for what seemed to be a mild irritation on her part. I picked the topic up in the next session, saying quite explicitly that I don’t want this gender debate to remain something based on “cultural” difference, notably with me, one of maybe four whites in the room, and the only European – it should be, and is, bigger than that, and I mean it. “Culture”, too, is a choice – my view.

Campus is a lively place. Various political and religious and other groups use it as a platform to gain attention and members, and on most days you can here one or the other group singing and see them dancing somewhere.

Let me also include a sorrowful note on another challenge that South Africa has been facing for years now, xenophobia. Roughly a months ago, a Tanzania PhD-student got killed by a taxi driver just outside Sophiatown residence around the corner from me. The student was wearing a traditional African attire that would show he is not from South Africa. A lot of the crime and other troubles here are blamed on immigrants from other African countries (so-called “makwerekwere”, which is said to be “imitative” of their languages), and this cost numerous people’s lives already. The CCTV footage in this case shows two students running away from a taxi, the driver though chases them and rams one of them into the fence of the residence. This is were I passed by a day or so later, noticing the flowers and the damaged fence. Here’s an article on the incident.

While I am still trying to get permission to teach at least one of the courses I had originally planned, I just finished teaching Hamlet for third-year students. A whole new experience, not least because I had never taught Hamlet before.

UPDATE: In the meantime I have given a talk on “Teaching Latin, teaching morals, emancipating English: Cato’s Distichs in England”, and enjoyed participating in a reading group in which we discussed Alexander Beecroft’s An Ecology of World Literature: From Antiquity to the Present Day with an eye on its relevance for African matters, under the guidance of the wonderful Liz Gunner.

* * *

source: https://www.wits.ac.za/site-assets/footer/facilities-and-venues/events-at-wits/

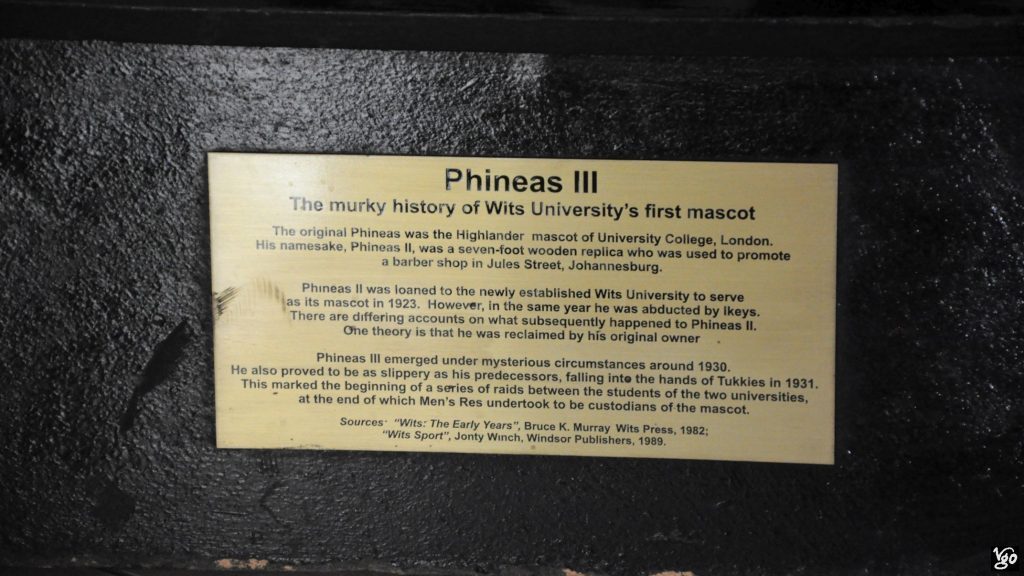

University of the Witwatersrand, a.k.a. Wits

Wits – what a name for a uni, I thought, and I thought in English! And then I found myself corrected, because it is an Afrikaans name after all, and hence pronounced /vits/. But jokes aside …

Following a lovely lunch date with Prof. Victor Houliston, Chairman of the Southern African Society for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, I had the pleasure to give a talk on “The Company She Keeps: Catherine of Siena in England” here (UPDATE: the related paper is now printing for Anglia). It was so well received, I was incredibly happy about my first proper academic talk in a long while. There’s more to come, and I may repeat it in Pretoria perhaps.

Wits is the third oldest university in South Africa, with an admirable history and quite a number of famous people who graduated from here, or at least attended: Nadine Gordimer and Nelson Mandela, to name but two. Here are some pics of Wits Club – old builidings in a Cape-Dutch style, which now house a restaurant and pub and rooms for various functions.

Besides that talk, I have given two classes on The Dream of the Rood, and I am happy to consult with two students on their M.A. and PhD projects, respectively.

More pics UJ