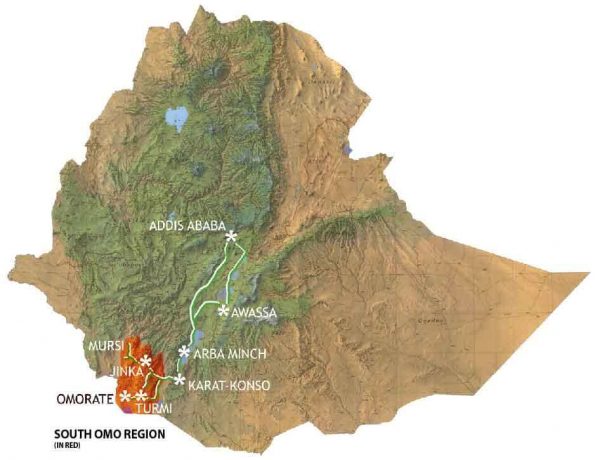

Ethiopia’s Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region along with the area around Lake Turkana in northern Kenya is one of the candidates for being the cradle of humankind, as some major discoveries that have been made here suggest. Since it is also a region with an incredible diversity in tribal cultures, it has been referred to as a (live) museum of human cultures. I found traveling here truly exciting, though not free from major challenges. I don’t mean the usual challenges of logistics, food and health or such like, even though they are more pronounced here. Rather, traveling here has exposed me to significant questions concerning the role of tourism, and tourist-tribe members interaction in a region where ritual infanticide and the ritual whipping of women is practiced. I have written about this in a separate post. So here’s a first glance only.

When I arrived in Addis, I wasn’t quite sure yet what to do, whether to go to Lalibela, how to do it, and so on. Eventually I decided to do what I had been longing to do for a while: visit pastoralist people. The opportunity had been there, in northern Uganda, or I could have gone to Botswana and Namibia. But here I was, at the end of my journey, and a new opportunity opened up, it would become one of the highlights. I’d arrived in Addis last night, now It was Monday evening, and I booked a flight to Jinka, and would take it from there.

Jinka is a small town, and the last place where you can find an ATM and some other facilities you may be used to, for instance a small hospital. Go further south, east or west, and these things will no longer be available for several hundred miles.

selling teff

Junka also has a market on Tuesdays, and while local people are doing their business, and some Hamer and Banna people are in the mix, every once in a while some Mursi enter the scene and try to extract some money from frangi, as white people are called in Amharic (apparently borrowed from Arabic, where the term originated during the crusades, due to the large number of franks ‘Frenchmen’ among the crusaders).

Here are the trips I went on:

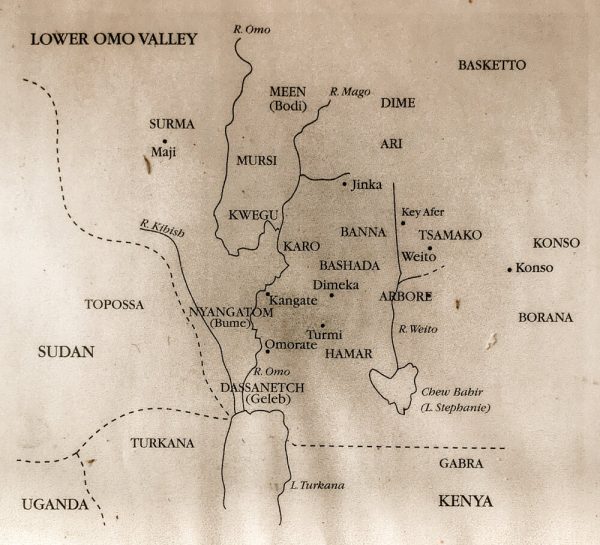

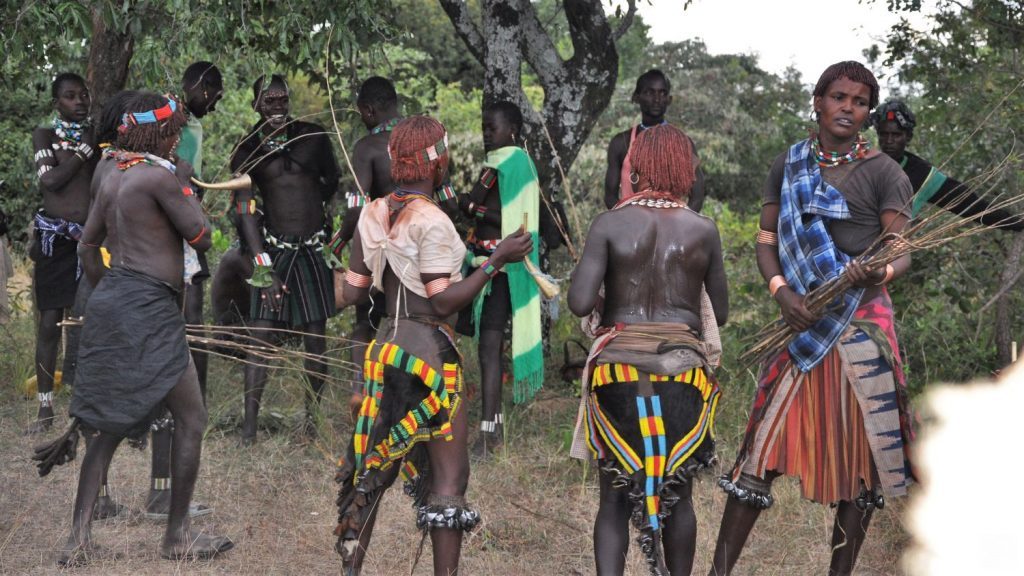

The tribal diversity is stunning, and it is not easy to keep track with who’s who. However, all tribes share the fact that they are Nilotic pastoralists, and thus related to the Maasai in Tanzania and Kenya as well as to the Karamajong in Uganda, and Turkana in Kenya. Some of them actually seem to stem from Maasai, and may have migrated back north. At some point I realized that they share two features: they don’t use drums unlike elsewhere in Africa, and when dancing their movements, especially their bottom movements, don’t go down towards the ground, as I would see most dancing Sub-Saharan Africa. Instead, they jump.

On the whole, I found their interaction rather harsh, and I wonder if it reflects the harshness of the environment they live in? I know this sounds like a naive assumption, but then again, why not? A lot of their customs may be read as preparing the members of their families for a rough life that will expose you to pain and sacrifice. Could the various skin modifications and other rituals be forms of toughening up everyone who wants to enjoy the protection and support of the group? A support that is absolutely vital in this environment. Needless to mention, as a rule they take legislation into their own hands, and some tribes have a king, and all of them various forms of social organization. Going to visit the Mursi, for instance, you must be accompanied by an armed guard. You don’t want to stand the chance of a conflict, which is always carried out physically, and which you will not win. In fact, you seriously run the risk of getting killed in the process. The Mursi and Daasanach are famous for their prowess combat. I wouldn’t take chances here.

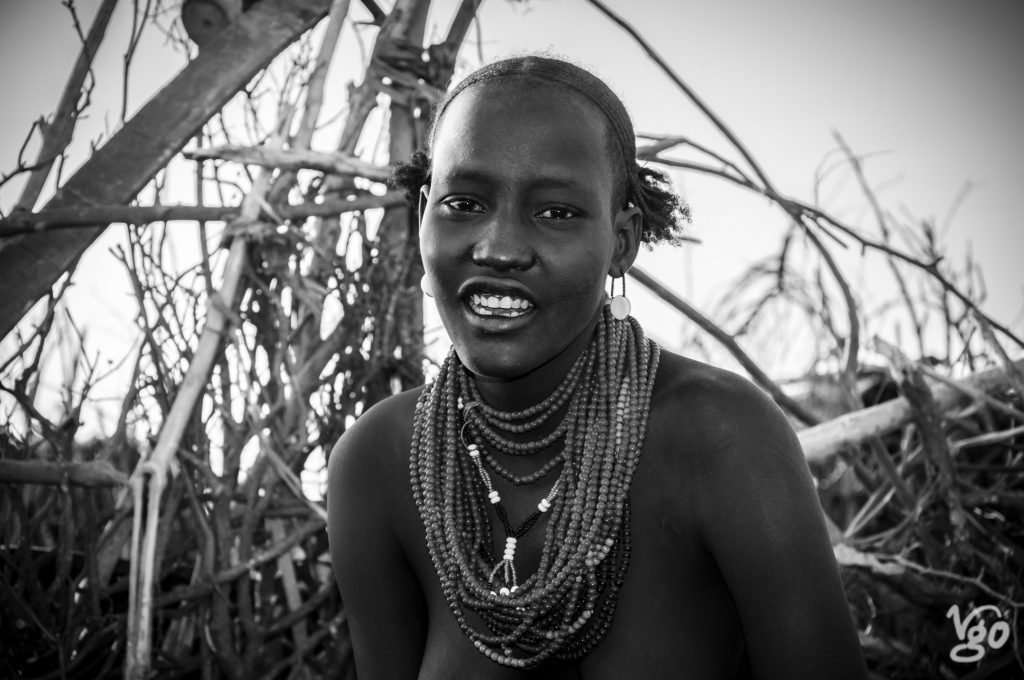

You may be surprised by the prominance of women, sometimes semi-nude, in the pictures. One reason is: the men stay decidedly in the background, are hardly to be seen in many situations. Another, possibly related reason: photography has become a major source of income for the tribal communities here, and we’re talking serious money. It is part of the problematic form tourism that has taken hold here for some time now. Two phrases that come to mind: Photo-prostitution, and Human Zoo. I tried as best as possible to get actual contact – you see some of my attempts through music in the other posts, and where it felt safe enough I gave my camera into local hands, hoping for a more local perspective, I don’t think it worked. And then. And then. And then I admit – there is a magic in some (not all) of the encounters, and a beauty many of the people that is incredibly tempting for someone who loves photography as much as I do. Eventually, I put pictures out here of people who asked to be photographed and asked to get paid – usually per picture, sometimes as downpayment of a higher amount per community. I’m happy to hear what you think about all this.

Today, all of them are also massively affected by climate change, and their traditional life styles are affected by their encounters with encroaching “modernity” in the form of the Ethiopian state, businessmen/women and tourists, though they may not necessarily be aware of there being an “Ethiopia” and so on.The Atlas of Humanity notes on the fate of the Mursi, for instance: “Today, the process of state-building in the lower Omo appears to have reached a new level of intensity, with the construction of a huge hydroelectric dam in its middle basin. This will eliminate the annual flood upon which the downstream population has always depended for cultivation and pastoralism and make possible large-scale commercial irrigation schemes. These will require the forced displacement and resettlement of thousands of people and irrevocably transform their environment and way of life.” (source)

A lot of useful information about the tribes can be found using the index of the Atlas of Humanity.

The toilet @ Jinka airport

On the way in, Ethiopian Airlines had messed up my booking. Apparently, they merged two flights, but forgot to update the passenger lists or so. At any rate, eventually I found myself on-board with a seat assigned to me that did not exist. But there was a spare seat, and all was well. It later turned out that somebody had opened one of the pockets of my backpack, but nothing was missing. Many others complained abouth the same experience. So when you pass through Addis Ababa Bole International, make sure your luggage is sealed.

On the way out, our flight, the only flight per day to go to Jinka, was cancelled much to the dismay of a group of Chinese tourists who had been foolish enough to book a connecting flight to China on the same day! To me it felt like the Africa of bad stereotypes was giving me a treat. I checked back in to my $5/room-hotel, though I upgraded myself to a $7.50 room in order to take a shower before my return travel to Germany via Addis. Only to learn that this night the hotel had no water. The next day the flight was delayed a couple of hours, and when we could hear the noise of the engines and got some visuals there was much excitement amongst us, a motley crew of stranded tourists and travellers. However, the weather was still bad, and as we were preparing for touchdown at Addis Ababa, the pilot all of a sudden revved the engines, and up we soared again into the skies, where we stayed cruising for another forty minutes. Anyway, we landed safely, and I rushed to my hostel to pick up stuff I had left behind, and then back to the airport to catch my flight. It was my last day in Africa this time around.

desperately waiting for a flight