Rocks are patient. They happily bear inscriptions of all kinds, and stoically accept whatever tale human imagination imposes on them. Or break, but that usually happens only a loooooong looooong time after an engraving has been made. Engravings may wither away, and the rock palimpsest becomes open to reinterpretation …

Before I turn to the more problematic examples below let me state that I love rock art, especially as made by BaTwa or San people here in east and south Africa (more on this elsewhere, and more to come), and I enjoy how people’s imagination creates stories around natural rock formations, for instance such as found in caves. Here are some examples from Sudwala Caves in Mpumalanga.

The Rocket

KFC chicken drums etc.

Horse head

Now, things are rather different with man-made structures. I have recently visited two sites (actually three, but two somehow belong together), and both have triggered quite hefty negative responses in me. So much so I have to write about them, and write jointly about them because they somehow are related, I find.

The Voortrekker Monument

Some cultures have developed a predilection for scattering the landscape with huge stone monuments whose major purpose is to signal “we’ve been here”, with a strong emphasis on We and Here. A local identity marker, hewn in stone. It’s a bit like my fellow Germans who place a towel at the beach in the morning to make a claim over a space, albeit for a future purpose, “I will be here”. Curiously, it seems that most indigenous African cultures refrained from erecting such monuments, at least not terribly huge ones, and I personally don’t find that that makes them less advanced or less civilized. After all, isn’t it strange to invest energy and resources into such a project? There seems to be a close link between a culture that uses writing and the building of huge structures meant to last for eternity. Or at least half of eternity. A thousand years? Anyway, many oral cultures seem to be so confident in preserving what is important to them by sheer mind-work, they can do without, or focus their efforts on more practical and yet spiritually loaded kinds of monuments, ones that also serve as calendars or astronomical observatories and such like. Tombs, for instance. But rarely ever have I found people so obsessed with their own past as Europeans and those of European descent (I believe owing much to nineteenth-century Historicism) and to some extent along the shores of the Mediterranean sea. I may be biased.

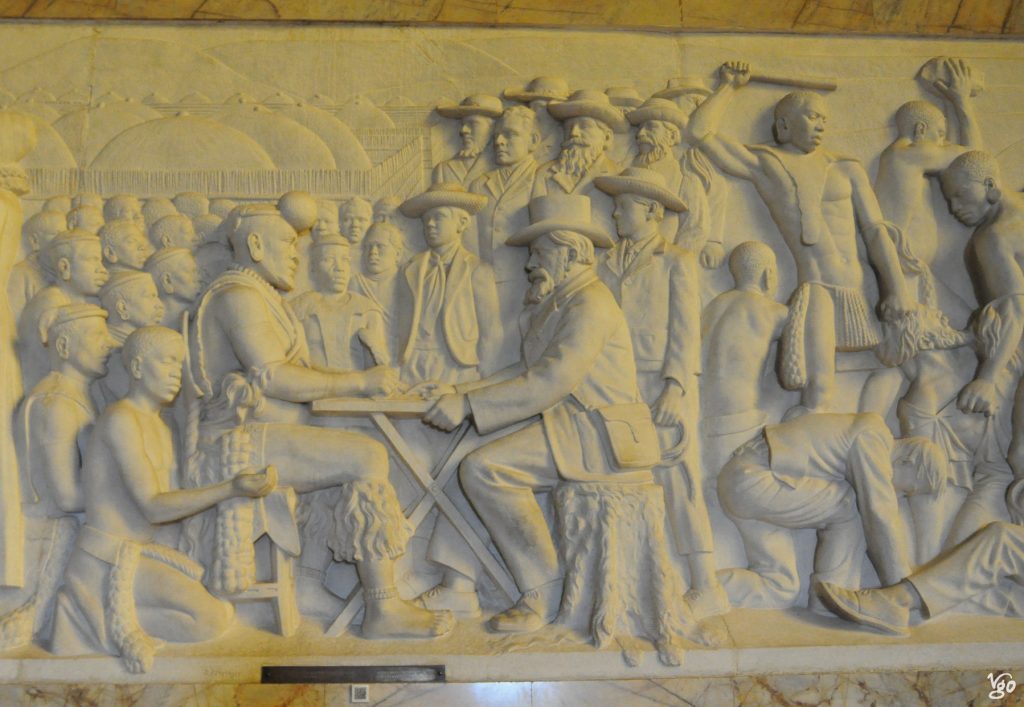

Anyway, the Voortrekker Monument (VM) is a structure invoking the past and thereby making claims about the present, intent to reach into the future. Erected in the late 1930s to commemorate “the Great Trek“, the migration of the descendants of Dutch settlers, or Boers, from the Cape region between 1835 and 1854, it is now a part of South Africa’s complex and uneasy history.

Without going into too much detail about the historical circumstances that led to its construction, I was utterly surprised how this monument to an emergent apartheid system, a monument to white – Afrikaner – supremacy, is left open to visitors without much or actually any critical commentary. What little research I’ve done indicates that the necessary work to contextualize the VM has been done. Yet, it is not here, not to be found in situ, where it is required.

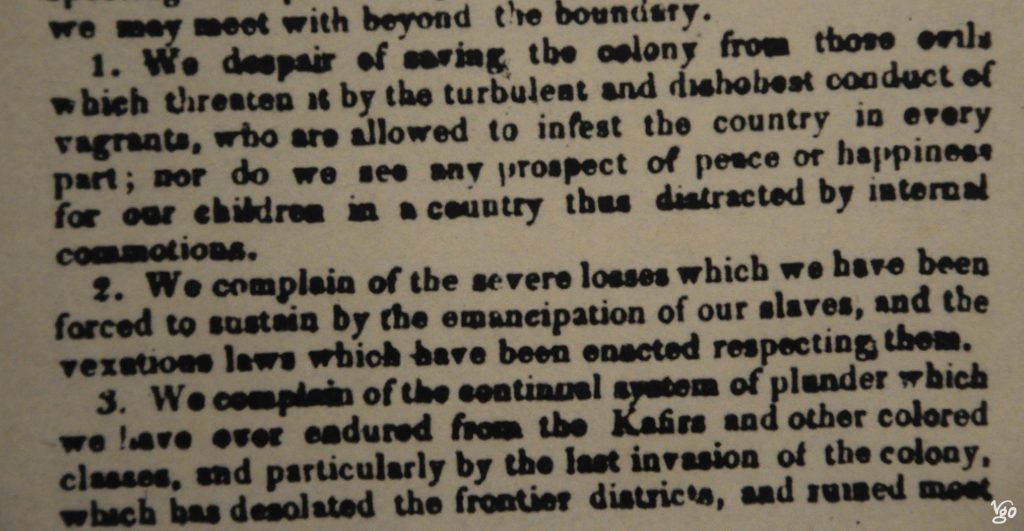

There is little critical discussion of why the Boers left the Cape, even though the fact that under British rule they had to abandon slavery entailed significant economic losses – or to put it differently: their economic gains could no longer be made on the backs of the indigenous people whose land they had conquered. See point 2. in their own proclamation, and their clear intention to maintain an apartheid system under point 5:

The 1938 torch flame still makes the loud claim that the Voortrekkers brought “the light of civilization” to what therefore must have been an uncivilized, dark corner of the earth. (You may want to consult the legions of articles drawing on Derrida’s “White Mythology” and light metaphorics in the context of (post-)colonialism, for instance by Shane Moran here.) It still does so without comment.

The 1938 torch flame still makes the loud claim that the Voortrekkers brought “the light of civilization” to what therefore must have been an uncivilized, dark corner of the earth. (You may want to consult the legions of articles drawing on Derrida’s “White Mythology” and light metaphorics in the context of (post-)colonialism, for instance by Shane Moran here.) It still does so without comment.

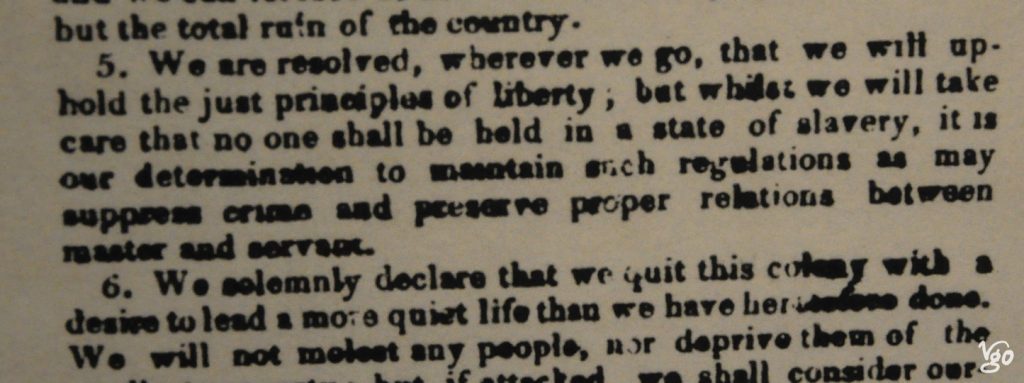

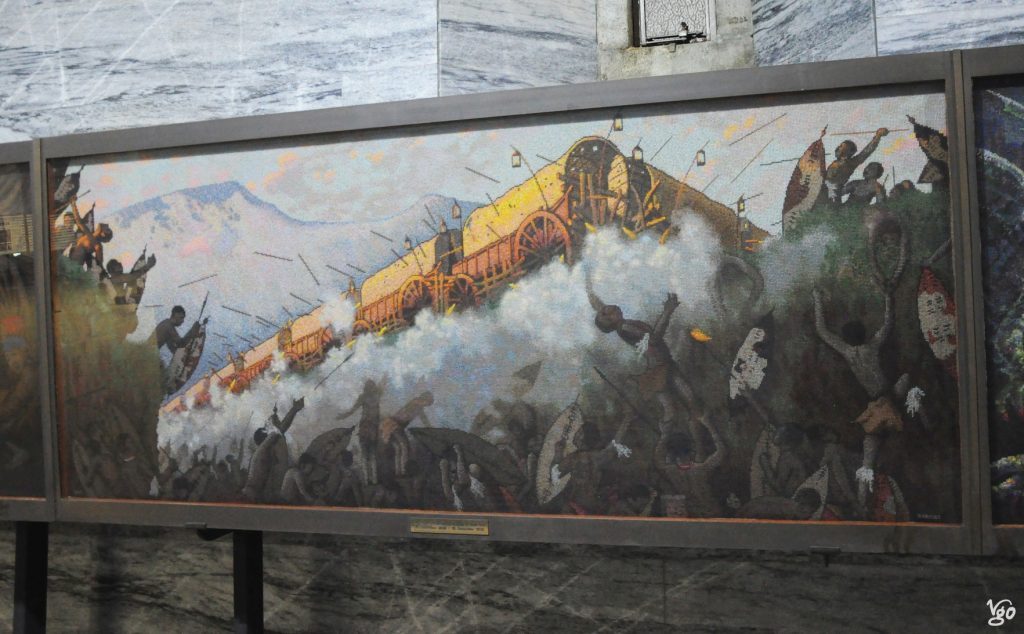

The exhibition has much to say about individual Voortrekkers and their families, Potgieter and Pretorius, and so on. With the exception of the brief mentioning of Zulu kings, the Zulus are Zulus are Zulus. Always a group, one like the other. A well-known racist strategy. The frieze in the “Hall of Heroes” (!) depicting the “struggle” of the Voortrekkers especially with Zulus has no commentary pointing out its biased depiction. It quite clearly shows a fight between “civilized” whites and “cruel black savages”. Look at the size of the people in the different frames: the Voortrekkers are large in an act of diplomacy, the Zulus in an act of violence. Note also how the Zulu “savages” kill women and children, of course, and note how “innocent” the approaching Voortrekkers apparently were. For weren’t they just looking for new land to settle on? Yes, and it wasn’t theirs, and no, it was not by coincidence that they were well-armed.

the fight between “light” and “darkness”

A German visitor like myself cannot help but notice the similarity to a famous German monument, the Völkerschlachtdenkmal (Monument to the Battle of Nations). Indeed, the VM was modelled on that German monument commemorating a battle of nations. Now, does not this shed light on the actual function, or at least an important level of signification to the VM? It is a monument to a battle between peoples – Boers and Zulus, Boers and the English, and still it gets away without much commentary.

the Völkerschlachtdenkmal in Leipzig, Germany

True, the architect Gerard Moerdijk was also inspired by Egyptian temples, and arranged the monument in such a way that a ray of light falls on the cenotaph in the bottom layer on 16 December – notably and in line with the above the day of the Battle of Bloodriver in 1838, a battle between nations, namely Afrikaner Boers and Zulu. South Africa’s complex history is beautifully highlighted by the fact that 16 December was maintained as a national holiday by the first post-apartheid government, and called or re-named rather as Day of Reconciliation. The speed at which the Mandela government jumped to reconciliation is, to me and in hindsight, quite breathtaking.

True, the architect Gerard Moerdijk was also inspired by Egyptian temples, and arranged the monument in such a way that a ray of light falls on the cenotaph in the bottom layer on 16 December – notably and in line with the above the day of the Battle of Bloodriver in 1838, a battle between nations, namely Afrikaner Boers and Zulu. South Africa’s complex history is beautifully highlighted by the fact that 16 December was maintained as a national holiday by the first post-apartheid government, and called or re-named rather as Day of Reconciliation. The speed at which the Mandela government jumped to reconciliation is, to me and in hindsight, quite breathtaking.

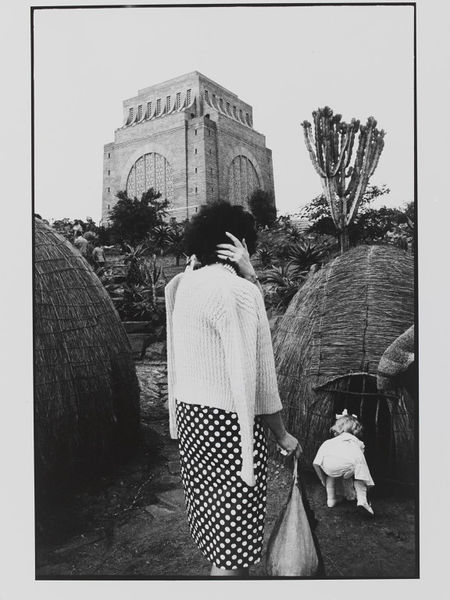

David Goldblatt’s photograph of the monument in 1963 is a brilliant illustration of its dominance over Zulu culture. Here’s a quote from an exhibition in 2015:

The chronology of this exhibition begins on the Day of the Covenant where, on 16 December 1963, Goldblatt photographed the dominating Voortrekker Monument with a replica of a Zulu hut at its feet. In the photograph a white child stoops to peer inside the hut, watched over by a supposedly caring adult. As Goldblatt has noted, “This day commemorated the vow taken by the Voortrekkers before the Battle of Blood River, that if God gave them victory over the Zulus, they would always keep this as a day of thanksgiving.” The photograph, then, is a study of dominance across cultures, and generations. (Source here)

Responses to the VM after 1994 obviously vary, but it is quite telling that while some black South African visitors to the monument found it insensitive and eliciting discomfort, a feeling of indifference to it seems to be dominating (read pp. 193-196 here) – this I find a pity. It would be a great place for black South Africans to re-appropriate their part in that history, and thus a perfect meeting place for the different groups that make up modern South Africa to hold the conversations that are urgently needed to make the “reconciliation” imposed on the country in 1994 come to life.

Let me add an anecdote, if it is one at all. I visited the VM together with my girlfriend Chimwemwe (see the pic on top) – black African from Malawi. As my phone failed me once again (long story!), I could not order a taxi. Eventually I asked a young couple to give us a lift to the Gautrain, and after some hesitation they did. In the car, some minutes into the ride, they introduced themselves and asked my name. I waited, but no, they did not ask Chimwemwe. They were a white South African couple on their return from the Voortrekker Monument, what did I expect? And no, this wasn’t the first time white people here ignored her presence. Well, Chimz can be shy and humble like so many Malawians, and eventually I introduced her, with what I hope was quite the right tone of disappointment to our hosts.

* * *

2. The Stone Circles of Mpumalanga and Inzalo ye Langa a.k.a. Adam’s Calendar

Mpumalanga, perhaps the province which features South Africa’s most stunning landscape, is also the scene of a people’s stunning achievement – the BaKoni stone circles. They are not typically advertised as a tourist site, nor indeed considered a significant part of (South) African heritage. That’s strange enough. If you’ve heard about them, it was probably through rather dubious channels – more on those below. It is in my view a good example of how academic discourse leaves (or creates) a void of “meaningless” fact, which is then filled by pseudo-scientific somehow more “meaningful” fantasies. This is a wider topic, especially in the age of fake news and other distortions of reality, and I am tempted to write more about it in the future. Here is but one example.

[Aerial view; image source here]

Once these stone circles have been pointed out to you, you may be surprised to hear that until today they are largely ignored by the public as well as by the South African heritage authorities – despite the fact that they extend over some 10,000 square kilometres along the northern Drakensberg escarpment and are amongst the greatest achievements of an African people. The only enthusiasts, it appears, are some archaeologists & co. on the one side, and some New Age “story tellers” (for want of a better word and for the sake of politeness) on the other.

There are different stories about those circles, and here I include what has become known as “Adam’s Calendar” (I hesitate to give you the Wikipedia link because of the content of the entry).

There are different stories about those circles, and here I include what has become known as “Adam’s Calendar” (I hesitate to give you the Wikipedia link because of the content of the entry).

Let me give you the “sober” story or stories first. There is good evidence that the stone circles are the work of a past local people, BaKoni or Bokoni (not even a Wiki!), who over a period of several hundred years until ca 1800 inhabited that area and created an agricultural industry that went far beyond subsistence farming. THAT is a major achievement, and an important argument in discussions about the alleged “inferiority” of African civilization before the arrival of Europeans. There are good brief accounts of the research here and here, and a brilliant long one here.

[aerial view of Inzalo ye Langa/Adam’s Calendar; image source here]

[aerial view of Inzalo ye Langa/Adam’s Calendar; image source here]

Likewise “sober” in my view is the account of the now so-called “Adam’s Calendar”, or Inzalo ye Langa ‘birthplace of the sun’ (Langa also being a boys name) near Kaapsehoop. This is said to be the name used for it by local people, as related by a sanusi, a spiritual healer or shaman. Apparently it was Credo Mutwa, a sangoma of quite some fame. Here, according to this account, heaven and earth meet, and the sun (or also son, i.e. man?) was created. What makes it a “sober” story for me is the fact (as I am currently willing to believe) of it being a local tradition, presumably handed down through generations. I consider local folklore a fact, though I cannot be sure in how far this particular account really is local folklore. Let us believe so for the moment although even this account reaches us through the channel that I shall talk about below. Ironically, on his own website Credo Mutwa doesn’t quite talk the stuff that he is credited for by others.

Over the last almost two decades these sites have been appropriated by new people who impose their own stories onto them – and who have created quite a bit of an industry around them, including a hostel, guided tours, books etc. Michael Tellinger, now a jack-of-all-mystery-trades, an anti-establishment everything from archaeology (he is a pharmacist by training with a degree from Wits university) to politics (as founder of the Ubuntu party), is at the forefront. I met Michael on my trip in Waterval Boven, and he is an overall nice guy, charming, friendly, as are the other people in the Ubuntu camp there. I mean it! Once Michael had learnt that I work on medieval literature and the history of English, he involved me in a discussion about Shakespeare and Hollywood movies. The bottom line of all of it: everything is a mystery. Deeply encoded subliminal messages are to be found in Hollywood movies as well as in Shakespeare alias Francis Bacon, and so on and so forth. And quite obviously, all established explanations are flawed, or fake, in order to keep the REAL TRUTH hidden from us. Or so the story goes.

Now what’s wrong with this? So far, nothing (or let’s say only something that Michael’s therapist should make note of, if he ever sees one). However, Michael’s efforts and the energy he invests in his projects erases the sober archaeological story (as well as the rather sober local folklore), leaving behind a palimpsest upon which he inscribes his own stories. I am not willing to repeat his version(s) here – they are all over the internet, on youtube, and published as books. You get a gist here, in which everything is connected – so much so, it’s all a big lump. To be fair, Michael does make it clear that his agenda is about freeing the mind by emphasising how we create reality with our minds. His mind, judging by what I’ve heard and read from him, is completely free of any constraints such as logic and reason and common sense. It is quite typical pseudo-science in which untenable claims are made: allegedly, there hasn’t been any research into these stone circles; all academic professors lie; allegedly “Adam’s Calendar” was discovered by Johan Heine (when in fact it had been known to locals all along); everything is the -est of whatever (oldest, greatest, strangest …); a sometime visitor at Harvard becomes a “Harvard professor”, and so on. And as Delius & Schoeman point out:

It [Heine’s and Tellinger’s book on Adam’s Calendar] provides a particularly striking (and lavishly illustrated) example of the kinds of arguments put forward by most of the antiquarian or ‘alternative’ explanations that have flourished since the 1970s. These arguments are advanced with little, or no, reference to fact or logic. They run along the lines of ‘Let us speculate that such and such might be possible’. Then a few pages later ‘Since I have shown that such and such probably happened’. And then a little later ‘As such and such has been conclusively proved’. All of this without any connecting logic or evidence. [source here]

a displaced rock explained by guide Enos

In essence, Tellinger’s account is one of many that are inadvertently based on the assumption that Africans were unable to create great structures of stone, and so on. Outsiders – here ultimately aliens – are responsible for the achievements. Again, one may ignore this. However, having been there, having taken part in a guided tour and heard the ambiguous story (a mix of the sober local folklore and much of the Tellinger version), I became angry in the face of a white man imposing his completely unfounded fantasy on a stretch of a land and eradicating step by step a local story of local achievement. Tellinger, to be sure, is not an overt racist. In fact, he opposed the apartheid system with a song he wrote and whatever else. However, his racism is of the subtle kind, covert, and comes in the form of cultural appropriation (Ubuntu movement and party) and re-defining, as with the BaKoni stone circles.

In the meantime, this place attracts people who – it is claimed – experience healing and flows of energy, and considering their numbers and the hefty entry fees charged, there also seems to be quite some flow of energy in the form of cash. … Talking about which: Michael Tellinger’s Ubuntu movement is very much opposed to any monetary system, and if you feel you are getting mixed signals now, you definitely need some energetic cleansing! …

On a serious note, I do honour and respect people who seek spiritual and other, alternative forms of healing. However, I hate every appropriation and misrepresentation of other cultures for the sake of one’s own projections.

Oh, if rocks weren’t quite as patient! It is time for the South African heritage authorities to protect the sites – materially as well as from blatant re-interpretation. The stone circles make for a great contribution to (South) African indigenous history and identity, and should be put on the map so local communities rather than the likes of Michael Tellinger and his Ubuntu movement get a cut of the action.

UPDATE: John Oliver on Science blown out of proportion and such like. Brilliant job!