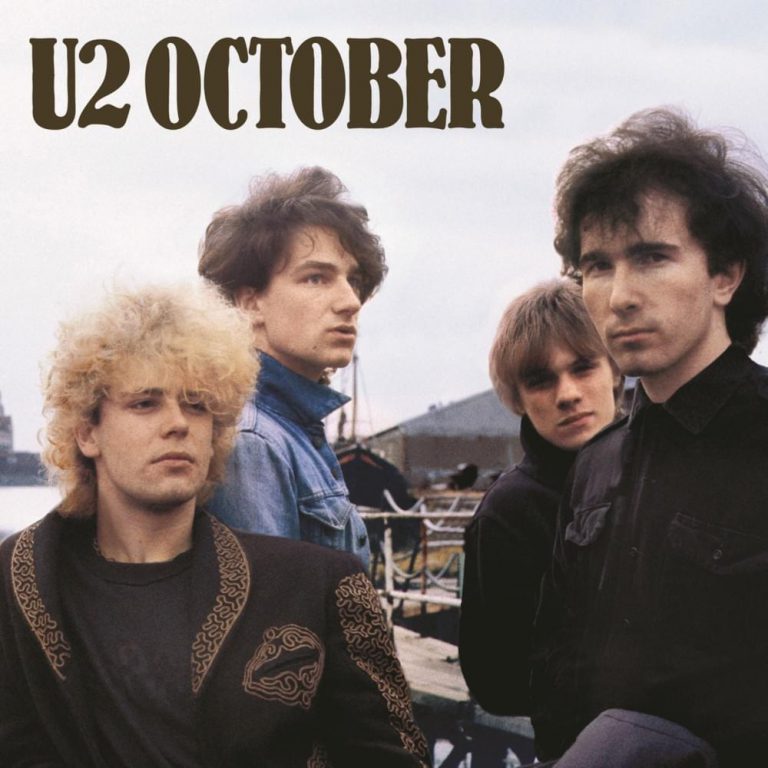

October and kingdoms rise

And kingdoms fall

But you go on

And on.

(U2 – October, 1982)

I have two beginnings for this blog post. I’m not sure I have a suitable ending.

Opening one: I’m just back from a discussion, with Naika Foroutan, about East-German migration analogies and prejudices against East-Germans, here at the local Literarisches Zentrum. “Here” means: Göttingen, West-Germany, for me, an East German by origin, my home of seven years now. Diaspora as well as home. “Here” also means: amongst an audience of, primarily, West-Germans. Naika Foroutan and host Robert Pausch are West Germans, too. They (“they”) speak about East Germans (“us”). Some of “us” are in the room. Their safeguard is the “objectivity” of the (social) sciences. “Objectivity” implies an object. An object implies a subject. Who’s who? I can feel I am one of the objects here, regardless whether I want to or not, and someone else assumes the role of the subject-agent. I observe.

I notice that: They speak about us, more than about themselves. They, them, us. Hence, an hour or so later, my question, when the discussion is open. Partly prompted by a remark by Foroutan (how minorities overcome being caught in identity bias), partly prompted by the previous speaker’s question on minority group’s identity anxieties (or so my shortcut for a more complex question), my question also partly prompted by my experience, an unwanted, not desirable, uncomfortably luxurious experience of myself as privileged in Africa: how do the privileged handle their own identity vis-à-vis identity anxieties raised by so-called minorities? I phrased it somewhat differently, and threw in the observation that a social majority of “normative normality” often seem to slip through one’s fingers when asked about their identity. I should have been more provocative: Foroutan’s fairly exhaustive answer included lots of very informed aspects, except what it could mean for a privileged West-German normative normality-culture to face that question. … Many other, very good questions and many more thoughts and talks with some friends later, I noticed all the more how helpful it was for me that Foroutan has a migration background herself (I checked, just to be sure, beyond her name and some side remarks about perceptions of Iran). I’d let her get away with things, I’m more inclined to buy some things from her that I wouldn’t from moderator Robert Pausch. I know virtually nothing about him, but suppose he’s a nice, bright, well-meaning guy and so on, and yet there’s something in the way some remarks are phrased that, in-between the lines, in-between syllables, speaks the language of privilege. One example: an East German acquaintance of his remarks on her feeling of loss seeing how Potsdam, her hometown, has been restored to some historic Prussian splendor that involves the loss, for her, of more homely features, the loss of home. For me, such a remark triggers: full stop. Period. Pausch, on the other hand, needs to ask about how to define such a sentiment as to its symbolism or what what. Containment. Defining. This, exactly, is how I experience privileged normativity on the (my) unpleasant receiving end. In how far do THEY create minority group identities through asking those questions? In fulfilling THEIR need for containment and defining? Somewhere in the midst of this and other points of discussion, Foroutan brings up the example of the fish in the aquarium: the researcher is wont to describe the fish, the water, etc., but not the container. This, her analogy, is how normative society acts (this is lit!). For me: yet another instance that she gets IT. … I do ask her later on, privately, why she’d say she was relieved that her current talks were well received not because of her person, and thus her migration background, but because of her work? I still find that her approach to her research, or at least the way she presents it, has an authenticity to it that makes it credible and makes me feel less “objectified”. Her response was welcoming, and she mentioned something along the lines of joint alliances (solidarische Allianzen) that emerge amongst groups of different migration backgrounds.

Without 9 November ’89 I would not have been here – in so many ways!

Border, eastern side

Dad fakes an escape across the insurmountable border fence

Walking the border

(Pictures taken some weeks after the border was opened and most of the mines and other dangerous stuff removed)

Opening two: It is Thursday, 9 November 1989. Apart from the fact that this is the most loaded day in all of German history (a revolution in 1918, a failed attack on a still fairly unimportant guy named Hitler in 1923, horrible pogroms, largely the destruction of Jewish life in Germany in 1938) – apart from all that, we’ve seen thousands of fellow citizens fleeing the country, we’ve seen mass demonstrations and the overturn of the government in recent weeks. Honecker is gone. Mielke is gone. You can organize a demonstration and don’t go to jail for it. You can say what you think of the government in public, in my case and at my age: at school, and don’t have to fear repercussions. A few days ago only, we held the lord mayor to task at our school on behalf of all local high schools. Moderator: yours truly. A few days later he had to resign. We can feel the power, and the slogan is “Wir sind das Volk” – we are the people! Now there’s so much stuff to work through, to organize anew. We gain access to the secret service strongholds, step by step. Babysteps. Nothing is well thought-through, nothing really is familiar. New-found-land. That’s where I’m at. I get the idea of socialism, I always did, maybe even communism, I feel we’re on the right side of history, and yet the government fucked things up – now it’s on us to set the record straight. (Thirty years on, in 2019, I feel very similarly.) A few weeks later on, “We are the people” was turned into “We are one people”. The nationalist unified-Germany agenda was set in motion, and the rest is history.

Thursday 9 November was a regular school day, and on this particular day we had planned to watch a documentary (or was it a reading? – I forget the actual format: so much was going on!) about an East German dissident whose name I hadn’t known just a few weeks earlier. Walter Janka‘s Schwierigkeiten mit der Wahrheit (Truth anxieties) had just appeared in print, and we went through some of it in our informal reading group from six till half seven. I reached home at around eight, tired. Quick supper, and I went into my room. Around half past eight my mom knocks on the door and enters my room: “On the news, they say the Wall is open.” … [Pause] … I say: “Really?” Okay. … And turn over. I’m tired and I want to sleep. Out there, somewhere, world order is being turned upside down, but I’m tired because there are so many things we need to sort out here. Here! On that night, I have no time, no energy for international affairs such as the Fall of the Berlin Wall which puts an end to the Cold War, to the division between East and West, to – you name it.

Come next morning, 10 November, I go to school as usual, around 7 a.m. I park my S51 (see above) at the school’s parking lot. A guy from another class turns up, beaming, and says: it’s true. He’s just been to West Germany. Went there on his motorbike, drove those 35 or so kilometres just to pass the border posts, made a u-turn to turn up at school. What? I mean, a week ago, a day ago, he would have been shot dead or, if lucky, imprisoned for a long time for the attempt only! Usually they’d pick you out once you reached the 5 km-zone before the border that was already out of bounds for average East Germans. I say this from experience. And just in case you don’t know: the guys of our own army would shoot us, not the “Western enemy”. Earlier that year I had to show up for conscription for the compulsory army service, and when during the interview that followed the medical check-up I said I wouldn’t shoot anyone trying to leave East Germany, not ever, the officer in front of me shouted at me saying they’d never make me serve at the border. Me (silently to myself): Result! You don’t leave East Germany alive unless your government approves of it! – but count me out. … Six school classes later on 10 November I joined a long queue of people outside our local police station, all of us willing to get a visa to “Go West”.

The story of the rather chaotic announcement made by Günter Schabowski: This, to me, is the ultimate expression of powerful negligence: you open that fucking border in passing. You m****fuckers. A border where hundreds of people lost their lives, and in many respect the lives of more than 16 million people were limited and held captive willfully. … One of the greatest challenges for everyone who’s grown up under a suppressive regime is to cope with the feeling of embarrassment of having allowed that, in whatever miniscule ways, to have allowed that to happen. (You people from outside of that experience, sorry, and please don’t take it personally or do if you must, you don’t get that bit.) … Schabowski’s helpless gesture at this press conference is, for me, the necessary embarassing collapse of East Germany: with a disorganized, half mis-understood, half sneaked-in phrase he wipes away the most signifiant material division of the Eastern and the Western world. Years later, I attended a talk by him – it didn’t help. I still feel the embarrassment. You fuckers held us captive, and we allowed you to, eish ………….. (I’m all emotional now, and I see no point in pretending otherwise. It’s … big. It’s embarassing what a small act it takes to make it big. I’m not entirely sure I make sense now for you, but for myself I do.)

I still do not have all of the details, but for all I know my grandad spent some two years in secret-service jail being accused of helping someone flee the country, and my family was observed by the secret service for some time for the same reason. Applications to have access to the secret-service files still are a delicate issue for my family, and for many families: Who did talk? Who betrayed who? Now that my family have given me all the documents to substantiate my rightful claim to look into it, my last request to have access to the files was answered with the generic response that it may take up to two years for an appointment. Patience is a necessary virtue.

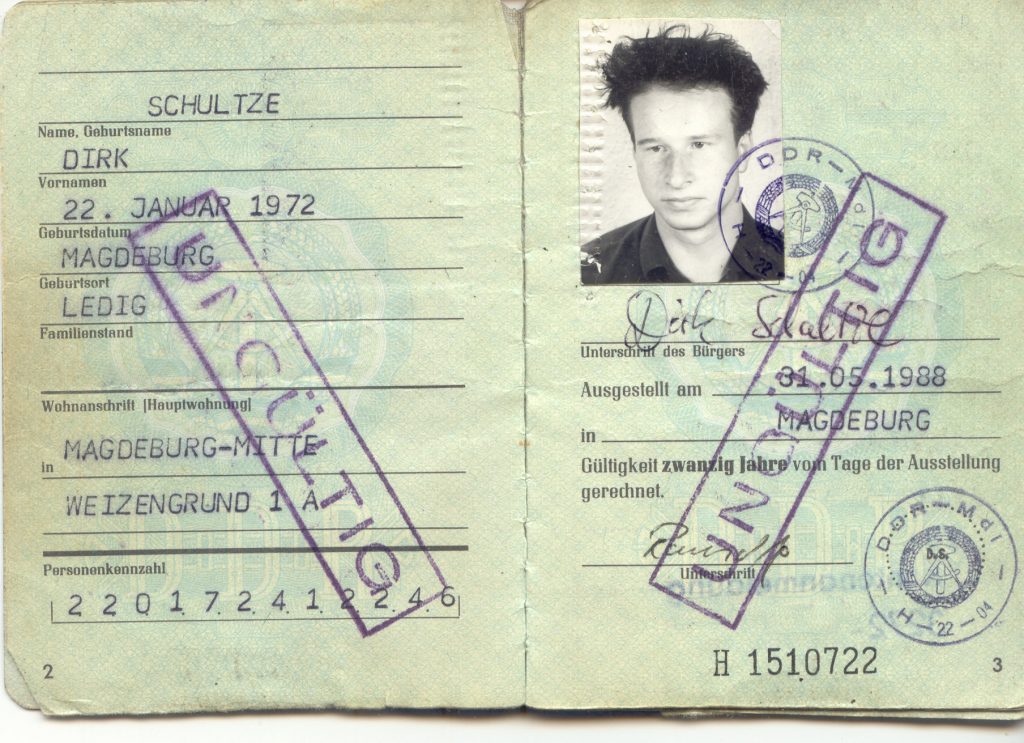

As chaotic as things seemed, it also seemed we needed visas to be allowed into West Germany. Exit visas by our own government. There was no need for entry visas because for West Germany, East Germany was not an entity. We were theirs, we’d been theirs all along. They never recognized me as an East German – or properly speaking: a G.D.R. citizen, but without even asking claimed me as one of theirs.

After school, I queued up – we queued up. After all, East Germany was still a community oriented culture! Some five hours later (I am nowhere near the entrance to the police station), the police want to close the station. Well, that’s them, but we’d been through too many demonstrations, truly risky ones, to let these government reps get away with it. People simply keep the door open and tell the police they won’t leave until all of us have visas. Period. And this is how it happens. The only way out for the officers is to do what we want. We are the people, remember? I have the ID booklets (not everyone had a proper passport) of my whole family with me, and another two hours or so later I have visas for all of us.

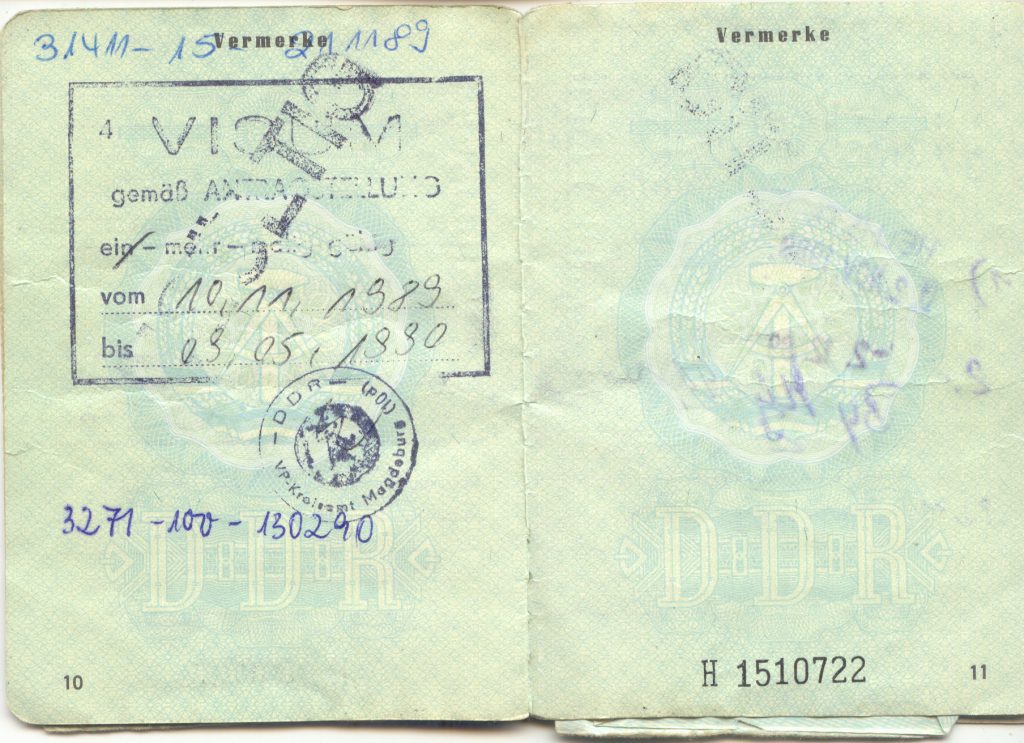

Mom and dad and my sister go the next day. I.e., they join a very long queue, the traffic jam at Marienborn border post to enter West Germany. My hometown, Magdeburg, is some 40-odd kilometres away from the border, and by Saturday morning the traffic jam has reached Magdeburg, goes past Magdeburg. A 40km-plus traffic jam of cars going West.

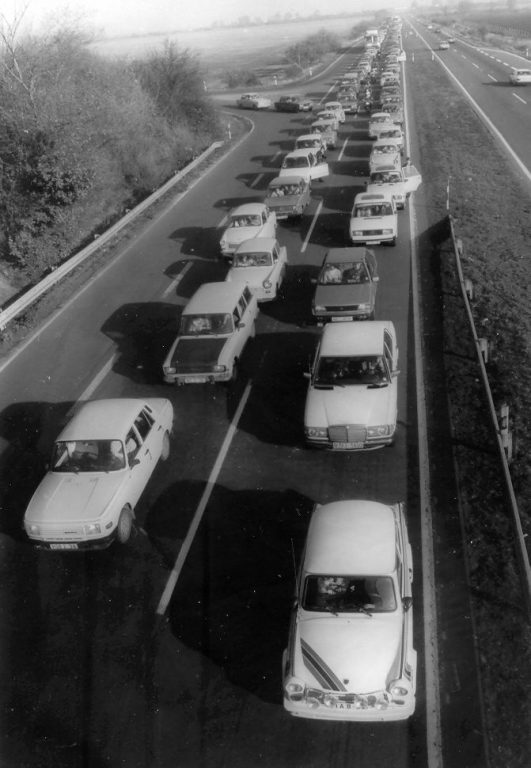

Some of my friends and I go a day later, and in order to avoid the traffic jam on the motorway, we take the B1 national road. I still remembered the traffic sign that was in place until 1978, clearly visible from our living-room window, pointing to Helmstedt, the nearest town in the West, 42 km away. That’s exactly what it said: “Helmstedt 42 km”. Never to be reached, just like the toys and other things advertised on West German television: see but don’t touch. When in 1978 my home village Olvenstedt was sucked up by the big town nearby (Magdeburg), a lot of local traditions, that traffic sign included, dispappeared. In my head I would still see it, though. I still do, actually. Hours of slow traffic pass, and later on 11 November, my friends and I are in Helmstedt, an unassuming small town in West Germany. We pick up the 100 Deutschmarks the West German government hands out to every Easterner upon their first entry (Begrüßungsgeld), and do what we’re meant to do: start our consumer lifestyle. Long story short: you’d find me in record stores (those were pre-CD days, vinyl days), and when I was going low on money plus a shop assistant failed to turn up, I concluded my first day in The West with stealing a record. I stuck a proper vinyl album, with all its 31.5 square centimetres, under my jacket. I am proud of it, I admit. I do not pretend it was the most revolutionary act (in the Che-Guevaran socialist-sense of the word), but I am being proud of it. I stole U2’s album October, which had intrigued me for a couple of years by then, but was not to be had in the East. A few years earlier, I had bought Depeche Mode’s Some Great Reward for 150 East German Marks in a black-market deal – a sum that would translate to around 400 EUR nowadays, meaning: I was prepared to invest into music, believe you me! And boy, I was well connected to get black-market deals even in a permanent surveillance system as was East Germany. Hence, I allowed myself not to accept being let down by that West German shop assistant in autumn ’89. In hindsight I am all the more happy because: look at the lyrics of the title track. I mean, they couldn’t be more appropriate. (Though my motive to have it back then had something to do with someone called Jeanny …)

U2 October

…

October and kingdoms rise

And kingdoms fall

But you go on

And on.

Side effects

One: Before any of this, in September ’89, a group of Americans arrived in Magdeburg. They were college students, enrolled in art history, and for some three weeks they would be stationed in my hometown to study German art history before they’d move to Munich (West Germany) for another three months to accomplish their course. I was one of two chosen representatives of my school to meet up with them. Well, there was Chris, from Denver, Colorado (and if you’re from the Western part of the world you have no idea whatsoever how “Denver, Colorado” sounded in my ears back then!), and her and I got along nicely somehow. Long story short: with the massive support of a classmate’s elder brother, we pretended to organize sports matches. I organized a place for us to play in, and so we could meet up with the lot of them under the pretext of a vollyball match. The actual excuse was so elaborate, no-one involved could say No to this East German-U.S. American volleyball summit (or the heavy drinking afterwards). Anyway, a few weeks later, Chris travelled to Berlin to witness the Fall of the Berlin Wall, and then sent a letter to me with an invitation to Munich, where they were based. I accepted. Sometime in late November ’89 I went to Magdeburg station to catch a train to West Germany. Easier said than done. This was a totally new thing, and all the trains passing through Magdeburg on their way West were packed to the rim. I let two trains pass because there was hardly any breathing space left in them, but then it was well past midnight, and although the third train from Leipzig (further East) to Hannover (West) was packed as well, I saw a little space between two guys in the aisle, asked them to pull down the window from the inside, threw in my backpack and followed suit. The ride was cosy: there was space for exactly one person between the two of them. The guy on my left would lay his head on my shoulder for the next hours or so, but hey, I was on my way to Munich! Once there, Chris assigned me a space in a three-bed room, later filled by two other Magdeburg fellows, and we’d stroll through town. In Hofbräuhaus, one of Munich’s famous beer-drinking places, John or Jack from Toledo, Ohio, asked me stupid-drunk questions about the East. A day later, and additional welcome money from Bavaria and Munich in my pockets, me and those fellow East-Germans went to Austria – because we could! Or so we thought – we had to complain first with the West German border police when the Austrians refused our East German IDs, thus we made sure that the West Germans who’d always boasted their freedom of travel and who’d always considered us as “theirs” would hand out day-visas, and they did and it worked. Exciting as it was, I knew even then it was not really important. I had started organizing another demo back home, and that needed attending to, not any Munich what what affairs. One or two letters followed from Chris to me and me to her in Denver, and that was that. Back then, I already realized that if I wanted to enter the U.S. of A., I’d always have to lie: one of the questions in the application form asked for membership in communist organizations, and sure as communist heaven had I been a member of some of them! What would happen if I told the truth? Those forms never ask for personal comment, for instance whether you wanted to be a member, what it meant for you or some such. … I still find myself lying nowadays. For instance in application forms for my partner to be allowed into Europe. Since I want it to go smoothly, I put “Germany” where the application form asks for country of birth, even though I was born in the G.D.R., the German Democratic Republic – not recognized back then by “(West) Germany”, and denied by me now sometimes when things have to go smoothly. Trust me, I understand when people talk about “the colonized mind”.

Two: Mom, dad and my sister got stuck in traffic so badly that they reached the first town in the West, Helmstedt, too late to travel back the same day. They decided to spend the night in a suburb sleeping in our Trabant car, the prototypical East-German car. Early next morning, someone knocked on the window and invited them to have breakfast in their house. The beginning of a new friendship. In the course of the next several weeks and months, this random encounter becomes more meaningful, and when my mom notices that West German lady’s sadness at some point, my mom allows herself to ask the question, why? The West German lady, after some hesitation, starts answering: at the end of the war, she lived further East near the Polish border, where she met a guy, got married and had a child. The marriage went sour, she was treated like a housemaid, and eventually decided to leave. A couple of years later, she met someone else who had aspirations for a position in Helmstedt, West Germany. He moved there, she followed some time later – in 1961. Nineteensixtyone – you get it?! In August that year, the Wall was built, and that was the last she’d see of her child. He had stayed with her ex, and East German authorities refused to cooperate. In other words: for the past 28 years she had not heard or seen anything of her child. Now, with the border open, it all came back big time. Her boy would be a grown man by now, in his forties. … My mom was cheeky enough to fake a story of school reunion or some such story for East German government authorities, and within a couple of weeks she had his address and organized a family reunion after almost three decades.

Shit man, to this day, this story makes me cry ….