Everywhere I have travelled in Sub-Saharan Africa, the picture is the same: women busy themselves, day in, day out, to do most of the work, chores and otherwise. I may exaggerate, though honestly, I don’t think I do when I say that Africa is run by women, especially in those fields that are run efficiently. This, obviously, excludes politics and a lot of admin. There you have it, I’m happy to stand accused of exaggeration and over-generalization, because I want to make a point. I do not care much for explanations that include the word “culturally”, I just share observations. Cultural practice, in my view, is a choice, and no explanation or excuse for anything.

Anyway, it is part of my first experiences in the region to be woken up by women swiping the floor with their simple, short brooms that force them to bow down low. Is the lack of a stick a deliberate measure to make them bow down low? Dunno. Often between 5 and 6 a.m., you can here their swish swish swish as they wipe away leaves, dog/cat/chicken/goat droppings around the houses and from the veranda. For these are veranda days, here. This is where you spend the part of the day that is not filled by work. Which means, it is mostly men sitting on the veranda, because there is always something to do for the women, and not only the housemaids. Yes, in my experience every African family has a housemaid. She may be a cousin from the rural areas, or some woman you hire. There may also be security guards and gardeners or generally someone living in an extension of your house who simply makes sure that there is always someone around watching the property. But the housemaid, or house help, is quite standard.

Women are not only found around the house, but this is their particular domain, and a lot of men will not consider this work. In fact it has taken German legislation a long time as well to consider work in the household as worthy of pension schemes and such. I remember a discussion with a guy on Zanzibar about reasons why local women would fall for white guys. As I brought up the topic of work and pointed out the all-too-obvious difference between him and some guys lingering around the beach area versus a couple of women walking along the shore with bins on their heads, babies on their backs and baskets in their hands, he failed to see them doing work. Here you will encounter “culture” as an explanation, and it is not hard to see why. From a very young age, girls and boys are expected to help with the chores. But particularly girls are expected to carry on with that work when boys, perhaps after they start school, are “promoted” to “more masculine” tasks, or so the story goes.

True, I have come to appreciate having a house help, and if I can afford it I will definitely employ one. I know that some people frown upon this as pretentious, or part of a suppressive system, exploiting people and so on. I believe this very much hinges on how you approach the person doing work for you. Unlike other people I have seen, notably well-to-do local Africans, I’ve never found it difficult to express my gratitude for the work some of the ladies did for me – on top of the extra money for doing laundry or so. And I must admit I admire the calm and kind attitude you can often see in these women doing their work. Judith, for instance, a widowed single mother of two, lost two of her brothers this year, and although she had just returned from the last burial, she was kind and all smiles. I was touched and impressed hearing her story.

Naturally, I get to meet quite a number of waitresses and receptionists during my travels, and often learnt some of their life stories. To give you an idea, here’s the example of Fely from Uganda. Fely is a single mom. Like in countless other cases the father of the child vanished when the pregnancy became a fact. Now Fely has a six year old daughter, who lives with the grandparents an hour away from where she works in a hotel. The hotel provides free accomodation and a job – she starts at 6:30 and is expected to work till 11 p.m. Seven days a week. She gets a day off every two or three months,on which day she may consider spending a few dollars to visit her daughter, which needs careful consideration because her close to 24/7 job earns her only € 25,- ($ 28,-), half of which she spends on school fees. I could barely imagine what means to be in such a position. True, the work as such is easy and doesn’t need much qualification. Neither does it allow you any promotion, and also you have to put up with African business men’s attitude – more often than not they will look down on you, and tell you the coffee cup is to small and to bring thme “the one you’d give to your husband!” That must be hard for a left-alone mom.

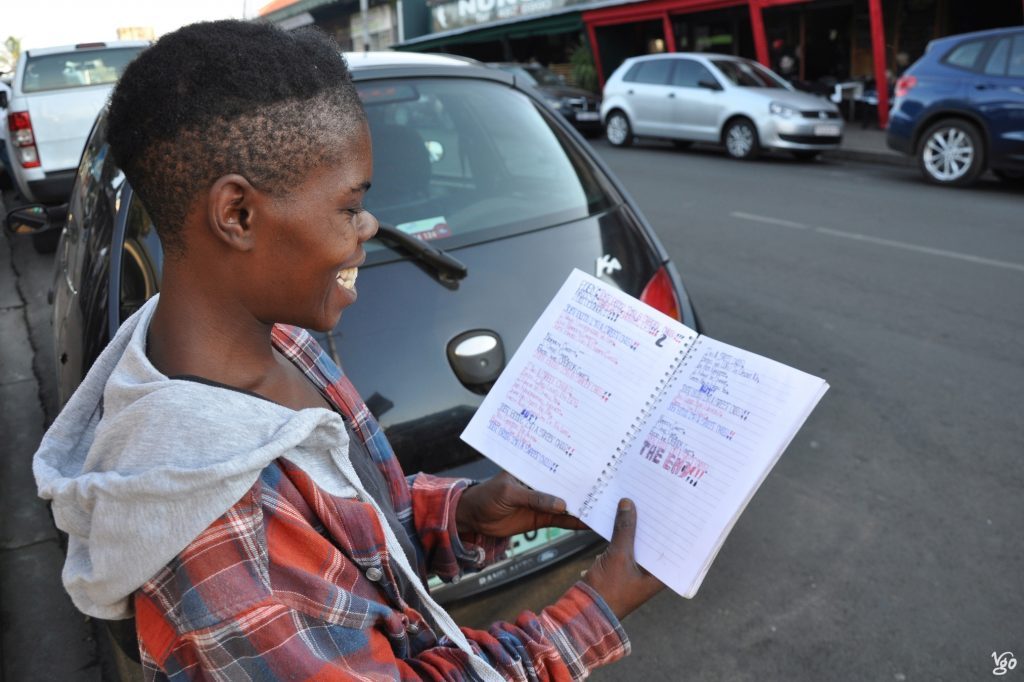

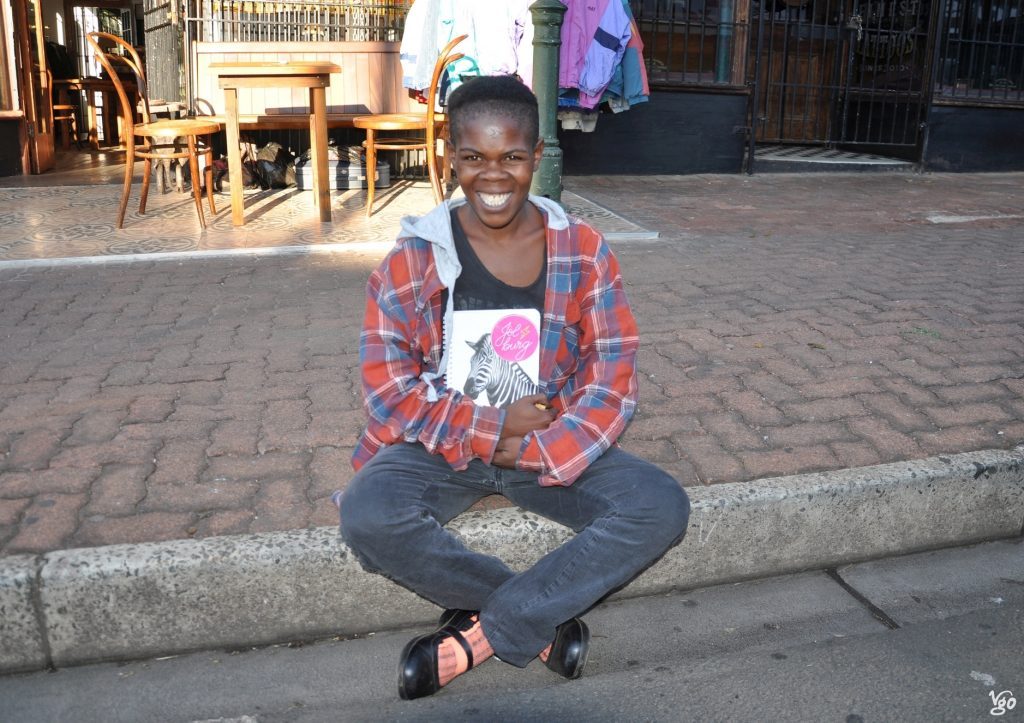

Another area of work are the fields. Very often you can see women with a baby on their back ploughing and planting the family field, and vis-à-vis their efforts I found myself too shy to take pictures. For one, I find it important to ask the person you’re taking a picture of first. Africa, along with other parts of the world, has a history of photographic abuse, and one can still see bus-loads full of tourists travelling through towns and villages as if they were in a big human zoo. The term “poverty porn” is apt, as used in a review of NoViolet Bulawayo’s We need new names, a book which at some satirically discusses why white people seem to be obsessed with taking pictures of African children. As the above picture shows, I have not always lived up to my standards, but I try and talk to the people in my pictures if possible and ask for their permission. Not only do I get the picture I’d like to have in most cases, I also get a kind of connection with the person in the picture, and preferably the picture implicates my presence.

As yet my choice of work domains is very sketchy – I don’t show women in offices, the police and military (this will be difficult), nurses and doctors in hospitals, teachers, wild-life rangers, check-out girls in malls, sex workers, and so on. It’s a start only, and I will add as I’m travelling. The biggest surprise to me were women doing unusual jobs, by my western standards, such as working on construction sites or doing road works. The last two, as far as I could see, happen in Rwanda. More than once post-genocide Rwanda reminded me of post-war Germany, where it was vital to look ahead and build up rather than to confront the past, and the guilt and shame etc. attached to it. That would be left for future generations to tackle. Hence these Rwandan women in “masculine” work domains may be the equivalent of the German Trümmerfrauen, rubble women, who played an essential role in making the country inhabitable again, quite literally. One of my favourite pictures of this whole journey expresses this beautifully – it’s this one

Among my most memorable encounters were those with community projects such as the Chibote women, who had come to Lusaka to present their works, most prominently beautiful baskets, at the Lusaka Art and Design Show. They had found support in Johanna, a peace corps member, who told me that one of the biggest challenges was for the women to demand higher prices for their work. They were simply too humble. It was nice to see them enjoying their success.

I also enjoyed meeting the women at RedRocks Camp near Ruhengeri aka Musanze in northern Rwanda, where I had the opportunity to try my hand at banana beer making and basket weaving. Bloody hard jobs, trust me!

Not my video, still wanna share it – tearing up when I first saw it:

UPDATE: See also my post on the late Winnie Madikizela-Mandela with a lot female power!

R.I.P. Mama Winnie

To work independently often affords women a more powerful position in their families as well as in society at large, albeit for often very low wages. As is the case with the algae harvesters in Zanzibar.

Harvesting algae for the world market is a lucrative business, and while the turnover for the local women is small, it has still strengthened their position. The red algae contain Carrageenan, the food additive E407 in EU countries, an emulsifying and gelling agent used in gummy bears and cosmetic creams. On a good day one woman can harvest 500kg of algae. When dry, the algae lose half their weight. 1kg dried algae earns a woman 160 Tanzanian shillings, i.e. at the moment EUR 0.06. As usual, Africa provides the raw material for a low price. Once refined, the cosmetics cream with red algae extract, for instance, costs about EUR 125. More information and source here.

Here some more impressions:

Food

Trade

Yunis, Nairobi

Crafts etc.

Josephine, Ukunda (near Mombasa, Kenya). Only this place is her shop, for which she must pay rent. But what a jolly good fellow!

Admin

Other

with Sandra, the bestest house help in the world She was too shy to share in the braai (bbq), but insisted to do all the work.

Fanisa & Selo, invaluable house helps at Plumpudding. They insisted on coming over on the weekend to cater for my parents.

Gloria the Street Poet in 27 Boxes/Melville, Johannesburg

More Jo’burg scenes

Additions 2019

Fisher women at Karonga (Malawi)

Good morning my brother, let me first wish you a happy Christmas and new year. I have truly enjoyed your compiled pics about my sisters in the sub Saharan Africa. I see what our sisters or indeed our mothers go through. I can’t agree any further than what you truly observed. Women by any standard are the most hard working in our region. I wish those leaders with instruments of power could do better to change this trend. All we need is to empower these women. Give them the opportunity to excel in education no matter what challenges they face. Yes skill is needed but beyond this skill, they need education if the region is to develop. I live in Zambia and Livingstone in particular.You and I met at Maramba River Lodge and the short interactive discussion we had gave me extra impetus to do more for my country. I look forward to seeing you soon and share more. I wish you personal good health where ever you are right now. Stay blessed.

Thanks a lot! Merry Christmas to you too 😉