Thirty years ago, I was one of those who for the first time in East German history were allowed to do Zivildienst, an alternative service instead of the compulsory military service. I received the letter around 15 March 1990, three days ahead of the national elections that were my first (I had turned 18 in January) – and due to to the victory of the CDU were known to be the last of an independent East Germany. Months later, in the night of 23 August 1990, the East German parliament decided to join the jurisdiction and political structure etc. of West Germany. They submitted (sic!) their decision to the West Germans after monetary union had already become effective by the end of June, and a decision for re-unification had been agreed on between the governments. At midnight 3 October 1990, East Germany a.k.a. GDR seized being an independent political unit, and until then we were her first and last Zivildientleistenden.

My decision against joining the army was based on a range of experiences. For one, those 1.5 years (minimum service duration) of service, or 3 years (expected or “strongly suggested” if you wanted a place at university) would have meant an even more severe cut of one’s personal liberties than life under an authoritarian regime meant already. Plus, there were nasty stories of things that had happened to one or the other of your male friends or relatives that did not sound inviting at all.

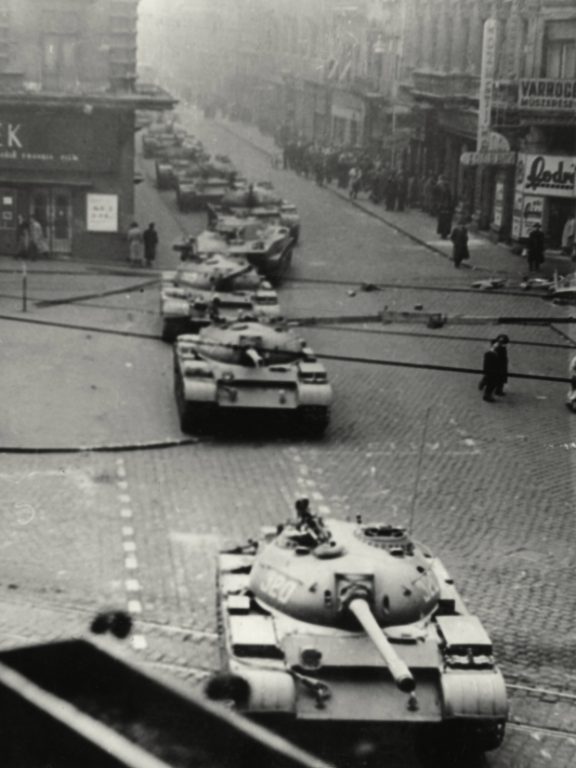

Such accounts were enriched by the worse stories about the Red Army, the “Russians”, or “Ivan”, as we’d call them irrespective of their ethnicity and origin within the Soviet Union (and with strong racial overtones). My associations with army service was deeply influenced by my memories of the “Russians”, some like these:

- Situated at an important crossroads that “the Russians” would use to drive to their maneuvers, I was used to seeing (and smelling) tanks and other big military vehicles driving past our house for hours at a time often. The cracks in the houses along the road were witnesses to the strain which that sort of traffic put us under. I vividly remember how more than once two young soldiers were dropped as posts at that crossroad, in the heat of summer or the cold of winter, and left there often for days – no toilet, no supplies. Especially in winter, we’d provide tea and sandwiches fearing for the worst to happen to them. They were not allowed to leave their posts – who knows what consequences they’d have faced if the crossroads had been found unattended! I had a bit of an idea: coming back from school, I once saw a tank running into a tree. Easy to happen, ours was an old cobblestone road, but no harm had been done, neither to the tree nor the tank. Except to the young pilot who was responsible for navigating it. He still had his head stuck out of the hatch when an officer chased towards him in a jeep. The officer climbed the tank and beat the shit out of that young guy who had his hands down all the time until he sank into the body of the tank, unconscious I guess. I was a young teenager, and quite shocked. It confirmed what we believed was true of “the Russians”: they were brutes.

- When three “Russians” escaped from the local garrison trying to make it to the West (my home town Magdeburg was only some 30 kilometres from the border), my uncle had been drafted once again. He served in a unit that eventually found those three guys hiding in a country barn. Since they’d used a hand grenade and fired some shots in a restaurant during their escape they were deemed to be dangerous enough. The “Russians” were called in to deal with their own. They came, and asked the German unit to withdraw. My uncle said that after this all you could hear was round after round of gunfire. Rest assured the mothers and fathers of these three guys will have received letters that, unfortunately, there was an accident in the course of which their son sustained fatal injuries.

- When I attended a summer camp near Magdeburg in 1988, in the middle of the forest, we also paid a visit to the local Russian garrison. Now you need to picture this: a few hundred soldiers, based in a foreign country that had brought unimaginable harm and destruction to their own country, on service for two years without holidays, all between 18 and 20 years old, now they are visited by young folk, aged 14 to 17 mostly, many of them girls. In summer dresses. Right. The night we our big party in the camp, with disco etc., and we were all in one corner of the camp, it turned out that once the party was over quite a few “Russians” had sneeked into a tent or bungalow here and there, on the off chance to get hold of a girl. Weeks later I learnt that there had been cases of rape with every group for years, yet because it was the “Russians” nothing was done. That night we figured that the few bigger guys amongst us and the three men of the fire brigade (the rest of the adults were women) would protect the camp that was only surrounded by a fence barely a metre high. We managed to chase some soldiers into the forest, and stood guard for the night. It was scary: we had big sticks at best, while the soldiers could be heard marching, singing and apparently drunk. And a few rounds of gunfire could be heard in the distance, who knows what that was. Some girls collapsed, and fled the camp in panic the next morning. We stayed, and nothing else happened, but this experience, too, formed my view of armies.

Then there were other experiences, unrelated to the “Russians”. Most importantly, it was the two times I had to attend pre-military camps, in the summers of 1987 (after grade 9) and 1989 (after grade 11). They were part of the school curriculum, and only the chosen few were exempt whose parents were doctors and found some condition or other so their son couldn’t attend those camps. I’ve written about them elsewhere. When I was called for mustering for the first time in spring 1989, I knew that guys from my school, a better-than average secondary school, were primarily drafted to join the border forces. So I sat through the interview with a young officer and told him how I found firing rounds with our AK47 at human-shaped targets very irritating and unnecessary, and that I would never fire at someone trying to leave the country. He shouted at me, saying he’d make sure I wouldn’t join the border forces. Result!

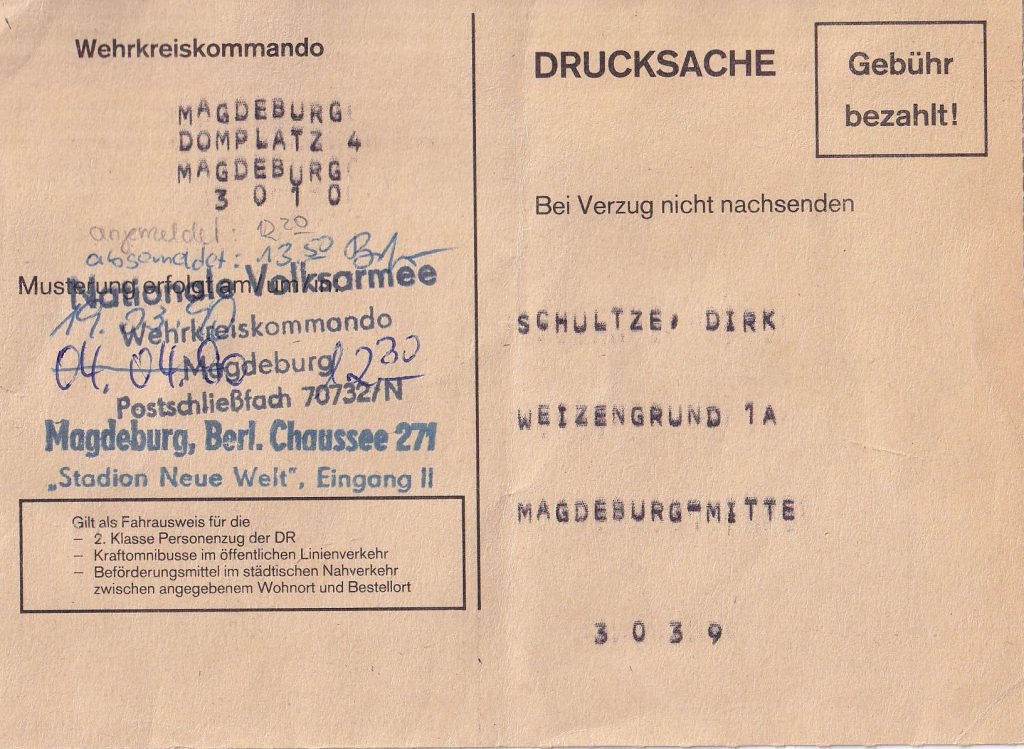

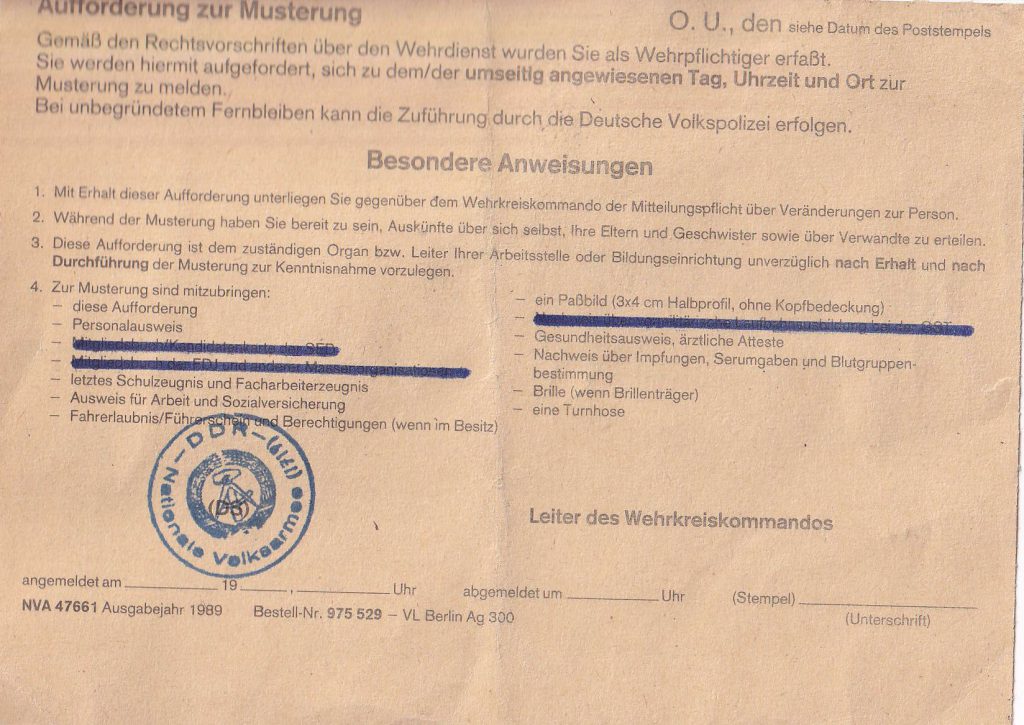

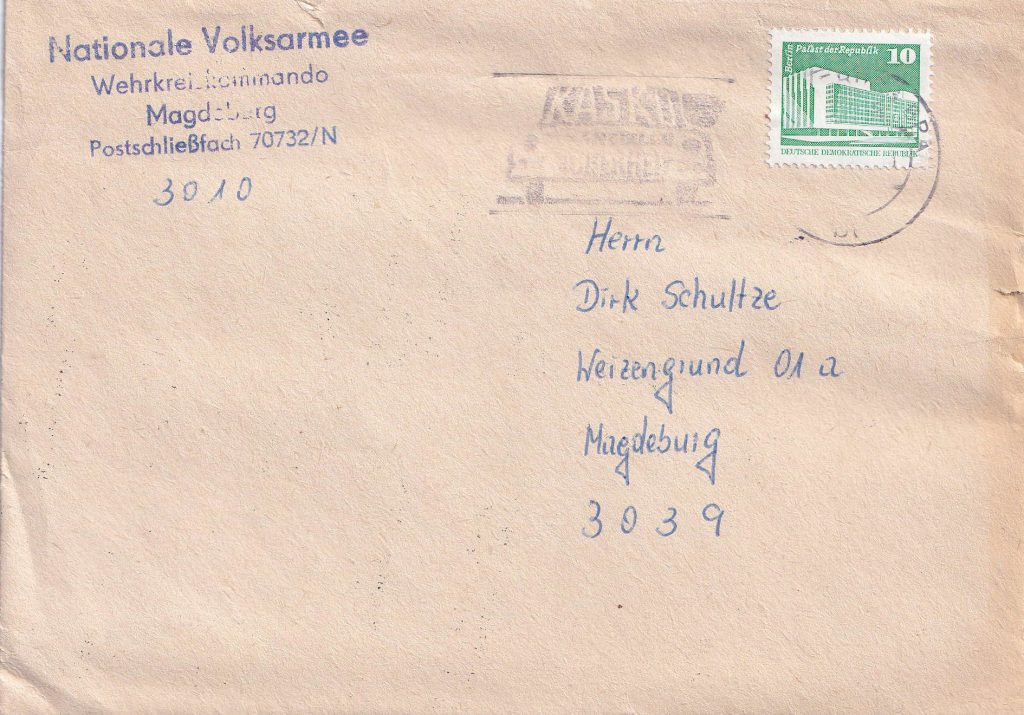

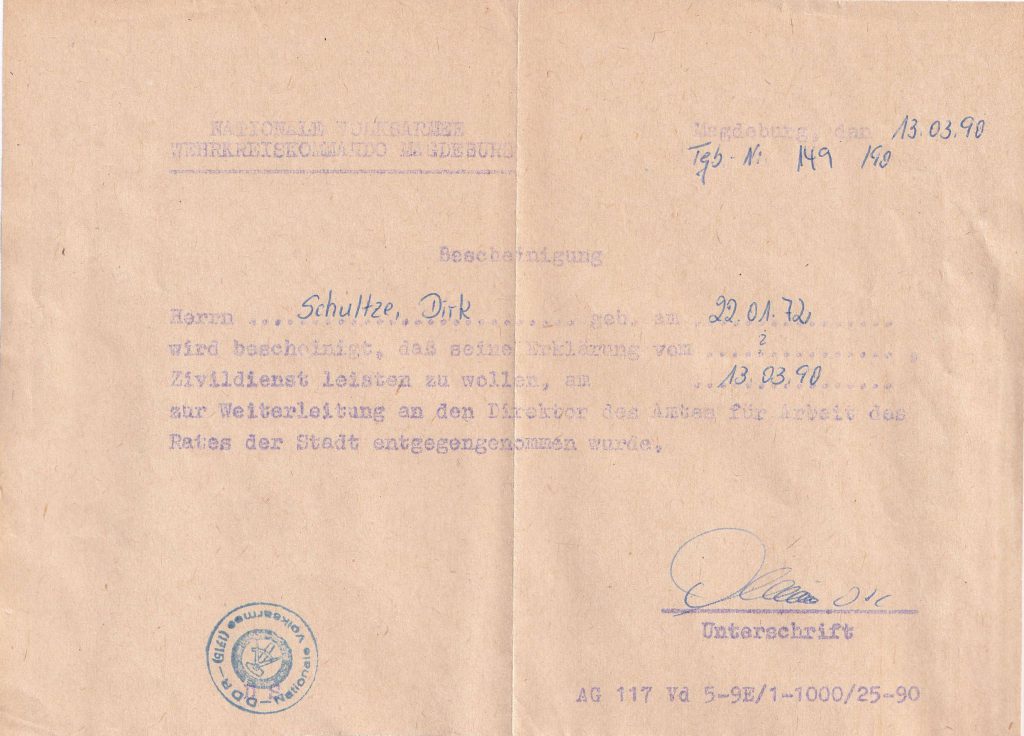

Then things developed unexpectedly, and rapidly. People were fleeing the country in huge numbers, there was the “Wende“, the Wall came down in November the same year, and come spring 1990, I had to attend another mustering session. Still in the mood of rebellion, I simply handed in a sheet of paper, with the handwritten note: “I won’t join the army”, and a few days later I received the note that I was chosen for the alternative service. Result!

We’d heard of the West-German Zivildienst, but I had no idea that in many cases guys were refused to do this alternative service. West Berlin was a well-known refuge for those who feared to be drafted against their will – well-known for Westerners, not us. Anyway, all that was far away from us because here in East Germany, we had just learnt to make our own rules and fight for them if necessary. With re-unification pending, things would change all too soon, yet some of our rules remained effective: East German Zivildienst was only 12 months unlike the 18 months in the West. One-nil for us!

While I spent the first three of those months at the construction site the former secret-service (Stasi) headquarters had been turned into, for the remainder I could join a school for mentally-handicapped children. Those nine months turned out to be great. My job was useful, meaningful, and full of experiences, too. I learnt how to feed a small child who couldn’t move her arms, how to change nappies of a six-year old. The school was a new invention – there had been nothing like it in East Germany. Thus quite a number of the regular employees were not fully qualified for the job, and for some it was even a refuge from a comprised job as some government official. That meant I was given a lot of leeway, and I was allowed to use my creative potential when working with the kids. to this day I am proud of how I managed to engage an autistic kid with no sense of there being other people in a group activity! And besides all this, for the first time in my life I earnt actual money, and quite a lot, considering I didn’t pay rent or food at my parents’ place.

That last year in my home town, 1990 to 1991, was one of the best of my life. Even though East German economy went down the drain, and I could see the trams and busses getting emptier by the day, and then the small newspaper shop closing down, still – Magdeburg was buzzing with live music, creative projects of all sorts, and the rebellious spirit of autumn ’89 lingered on for a while when the first Gulf War broke out, and Yugoslavia started falling apart. For a lot of East Germans, this became the time of both consumerism and anxieties about unknown things such as unemployment and poverty. And: the risk of falling prey to loan sharks and proper frauds (some of my parents’ friends lost huge amounts of money!). East Germany was being taken advantage of as a big market with 16 million people, that’s a lot of naive, hungry consumers. Well, I mostly stayed away from it, except for travelling, and in autumn 1991, when my service was done, I moved further east to Greifswald to study – not maths and physics, like my first enrolment from before the revolution of 1989, but German and English language and literature. Until today I profit from the experience of working with, and taking care of these kids.